The reader may have noted that one important occupational type seems to be missing, the creative artist, the genius. Some performers involved with the advent of rock including Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Elvis Presley have recently been called geniuses. At the time, however, they were not so designated, nor did they act the part.—Richard Peterson

Every one of my records means something. The label, the producer, the year it was made, who was copying whose styles, who was expanding on what. Don’t you understand? When I listen to my records they take me back to certain points in my life.—Barry Levinson

[The poet] is unlikely to know what is to be done unless he lives in not merely the present, but the present moment of the past, unless he is conscious, not of what is dead, but of what is already living.— T.S. Eliot

The question I want to address in this book would apply to any album. And it’s a question I’d think of as being rather Germanic, or even Swedish: what is it? Or, more earnestly, what is OK Computer? ‘IT’S GOD-DAMN OBVIOUS, FOR CHRIST’S SAKE!’ Sorry, what did you say there? If you said, ‘it’s an album’ or ‘it’s a record’ or ‘it’s a CD’ or even ‘it’s just music!’ (ah, sweet!), what set of references were you implying? Imagine language has you locked in its prison and, however above these things you may consider yourself, all you’re doing is selecting a word which carries on its shoulders a distinct history. So the term you choose involves not only the history of the recorded album as it had developed by 1997, when OK Computer was issued, its immediate past, and the longer past on record, but also, more speculatively, archetypes of musical form which may indeed transcend the fact that this happens to be a recorded album. Phew.

Still here? I’m especially interested in OK Computer because it appears rapidly, probably mistakenly, to have attained ‘classic’ status. Greatest album ever, that sort of thing. We’ll find out, or you will: sooner or later one of us must know. Sure, you have to be sceptical in the company of hyperbole, and claims like those are only a reflection of taste and a version of value but, all said and done, it’s an interesting idea to play with. So, at the risk of kicking off an academic area called something like ‘album studies’, I want to begin by considering what might constitute an answer to our opening question.

Since the invention of sound recording (Edison’s phonograph in 1877, Berliner’s gramophone in the 1880s), records have maintained a balance between the potential of the format itself and the musical material. Both before and after the invention of recording, musical material to some extent followed the technology available, while sometimes the technology adapted better to present musical material, ‘technology and cultural form’, in Raymond Williams’ phrase. From the start, records preserved moments of performance; by the late 1940s and 1950s, however, it became possible to present electronically-generated sound separate from those performed by voices or instruments and, through multi-track recording, for records themselves to become constructed artefacts in their own right. So the history of recording in its first half-century is of great performers and performances: Enrico Caruso, Duke Ellington, Leopold Stokowski, Bing Crosby. The second third of the century also becomes the story of inventors: Maurice Martenot, Louis Theremin, Pierre Schaefer, Les Paul, Robert Moog (eventually such pioneer individuals seem to disappear behind the corporate front). Later still, the record producers: Walter Legge, John Culshaw, Teo Macero, Phil Spector, George Martin, Brian Wilson, and, for this record, Nigel Godrich.

Against that sweeping background, this chapter selects one aspect as focus: the physical nature of the record, its format. Record formats change in various ways, some of which effectively disappear from view, such as a record’s durability (how easily smashed) or its speed of rotation; however, one aspect of change in format affected the content of the record directly: the length of time available to be filled. Before the invention of sound recording this was a very different matter, for notated music is dependent upon the readiness of intermediary performers to choose to present the music. For records the key formats have been, over the span of the twentieth century: 78 rpm, 45 rpm and 33 1/3 rpm, cassette, and CD. Shellac, at 78 ‘revolutions per minute’ (the number of times a record spun around the turntable), was the key format till 1948; 33 1/3 and 45, both vinyl, superseded and effectively killed off the production of 78 after what Russell Sanjek calls the ‘battle of speeds’ in 1948/9; music cassettes appeared in the mid-1960s and flourished (especially because of the Walkman) in the 1980s; and CD was introduced in 1982. By 1996, says Dave Laing, ‘the CD had replaced the vinyl LP’.

I want to draw attention to two particular aspects of the development of formats, based on excellent material found in the first volume of the Continuum Encyclopaedia of Popular Music of the World, published in 2003. One is the origin of the term ‘album’ itself. Keir Keight-ley writes:

’Album’ originally referred to an empty, unmarked container that was purchased for storing assorted 78 rpm singles. The containers often featured blank spaces in which to write the names of songs and performers, reinforcing an early sense of the album as a personal collection (like a photograph album).

Another is the presence, at the key, momentous points of format change, of ‘classical music’ itself, tied to the idea of how long music lasts. Keir Keightley on the 78: ‘While albums of ‘classical’ and operatic works began to appear around 1900, it was not until the 1930s that pre-packaged albums of popular music made their debut’. Dave Laing: ‘Attempts had been made, almost from the invention of sound recording, to find a means of recording more than a few minutes of music onto each side of a disc or cylinder. The impetus came primarily from among those involved with the recording of classical music who were unhappy at having to interrupt the flow of a symphonic movement when a disc was changed’. Even in 1980, when Sony was working out how long a CD should be allowed to last, the decision to extend to 74 minutes or so seemed swayed in the end by the thought of classical music, and not any old piece of classical music, either. Sony’s President Norio Ogha was also a conductor and singer, and in 1980 there were two outstanding issues with CD. One was concerned with quality of sound; the second, as John Nathan describes in Sony: the Private Life:

… related to size and capacity. Philips proposed an 11.5 centimeter disc, which would fit into an audio car system in the European market and would allow a recording capacity of sixty minutes. Ogha was adamantly opposed on grounds that a sixty-minute limit was ‘unmusical’: at that length, he pointed out, a single disc could not accommodate all of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and would require interrupting many of the major operas before the end of the First Act. But seventy-five minutes would accommodate most important pieces of music, at least to a place where it made musical sense to cut them, (I’m indebted to Dave Laing for this reference.)

It may be surprising to consider that CD length depended not only upon technological but also aesthetic considerations.

How a record is described, our opening question, appears to resolve several things: one, the technological artefact (record, CD, single); two, a pull between the album as a miscellany, a personalized invention (the photograph album), and something specially produced as a single thing; and finally something where length itself, like it or not, pulls us into thinking about this basic distinction of popular and classical music. Keir Keightley again:

Albums can be seen to expand the boundaries of popular recordings, whether in terms of the LP’s or CD’s superior technical fidelity, the greater length of material presented or, especially, an increased sense of artistic possibilities. More than merely a collection of songs, the album here is associated with ideas of complexity.

I want to propose a specific type: the CD album. As we’ve seen already, this was partly a matter of length. John Borwick on the vinyl formats: ‘The 12” diameter long-playing record plays at 33 1/3 rpm and provides about 25 minutes of music per side, well suited to longer musical compositions or recital albums. The 7” “single” plays at 45 rpm to provide about seven minutes per side.’ LPs could be longer: my ‘half speed mastering’ copy of Stephen Sondheim’s Metrily We Roll Along clocks in about 30 minutes per side. Dave Laing: ‘Because the grooves could be closer on vinyl discs, this LP could hold approximately 20 minutes of music per side. This enabled jazz musicians to record extended pieces, although in mainstream popular music the LP typically contained 12 tracks of three or four minutes’ duration.’

Clearly, the CD album expanded the available duration from 40 to 50 minutes maximum to about 74 minutes (an additional 50%), though its other feature—the eradication of the ‘side’, meant a huge increase in continuous music, from 25 to 74 (an additional 200%!). For the listener (I’ll step over the distinction between private and public listening), the latter increase is the one that counts. Simon Frith in Performing Rites has splendid examples of people getting worried that the shift from 78 to LP meant the end of ‘active listening’: Kingsley Amis considered the invention of the long-playing record ‘perhaps the deadliest blow’ for jazz, ‘doing away with the concentration and concision enforced by the 78 record with its three-plus minutes’.

A question of music history: was there ever quite such a hike in time as that offered by CD? Was the ‘heavenly length’ which Schumann heard in Schubert’s Ninth Symphony also unprecedented length? Were Wagner’s operas (a locus classicus) such massive advances in prolixity on the German opera of the day? I won’t stay for answers. However, when CD appeared, one surely was aware of change. My friend Andreas Broman wrote in an e-mail from Sweden:

When the CD phenomenon broke (I vividly recall the Brothers in Arms phenomenon in Sweden as well) artists felt compelled to fill up to 60 minutes in order to compensate for the higher price and, as I remember it, there were two ways of doing so: adding bonus tracks and extending the existing songs (much as with DVD films today). Hence the many 5-6 minute songs with enormous intros and outros (possibly midtros even). Like it or not, but discussing these things I usually bring up Def Leppard’s Hysteria from 1987, since I consider it an album very much rooted in its time and a good example of the early CD years. It has got 12 overproduced songs, half of which are over five minutes (shortest track is 4.04), it’s crammed with intros and effects and all kinds of time wasting stuff and the clock eventually stops at 62.38.

The Brothers in Arms phenomenon, to which Andreas refers, is the Dire Straits album of 1985 whose occupation of the British album charts of the day is a good signal of the arrival of CD. It first entered the top 50 album chart on 25 May 1985 and departed finally on 8 October 1988, a period which included a total of 20 weeks at the top. This was, evidently, the record which showed off your new gadget, the CD player, notably the great, ‘air-guitar’ entry in ‘Money for Nothing’. Other indicators of shifts towards CD were extensive hit compilations such as Bob Marley’s Legend of 1984; similar compilations of Roxy Music and The Police followed in 1986.

While at the time, the quality of digital sound on CD was hotly debated—Neil Young and Ry Cooder were notable sceptics—the assumption that individuals or bands could sustain levels of creativity offered by the time-length of CD can in retrospect seem the more debatable aspect. The frequency of the appearance of albums seems to have changed over the years: in the early 1960s, as pop acts, the Beatles or Beach Boys kept the product rolling. By the 1990s, British bands Elastica and the Stone Roses were noteworthy for taking time over follow-ups to their debut albums. Frequency isn’t the whole story, however, since musical material can be more or less derivative: those early Beatles albums contained many cover versions, and the period of invention on their part seemed to reach a peak and fall off towards the end. If, in the CD era, we examine a career trajectory such as that of Tori Amos, there does seem to be an awful lot of, well, creativity going on:

Little Earthquakes (1992) 12 tracks 57 minutes

Under the Pink (1994) 12 tracks 57 minutes

Boys for Pele (1996) 18 tracks 73 minutes, eight of which were taken by a remix of the track ‘Professional Widow’

From the Choirgirl Hotel (1998) 12 tracks 54 minutes

To Venus and Back (1999) 11 tracks 48 minutes, with a bonus 13-track live album at 75 minutes

Strange Little Girls (2001) 12 tracks 62 minutes—all cover versions

Scarlet’s Walk (2002) 18 tracks 74 minutes

This comes to a total of 82 original songs, give or take a few, and there’ll also be B-sides (filler tracks for single releases) galore which may well push the total to 90 and beyond. This is a great deal of writhing at the Bösendorfer piano, especially in a time and style where there’s no real sense of artistic convention, which goes some way to explaining zany creative outputs like that of Haydn or Vivaldi. More like Stravinsky or Miles Davis, Tori Amos really is making it up all the time! In perceiving this aspect, the CD clock was crucial: although track timings had been supplied for some time in parentheses on vinyl or cassette, one hardly thought of totting them up.

When finally I procured a CD player I was greeted by long-distance runners such as Prefab Sprout (Jordan: the Comeback (1990), 64 minutes), Tindersticks (Tin-dersticks (1993), 77 minutes), and Smashing Pumpkins (Siamese Dream (1993), 62 minutes, Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness (1995), a double CD at 57 and 63 minutes). Just sitting around for that long seemed a new thing altogether. On the other hand, I also remember for a time feeling diddled before the music even started if the figure on the clock came in under 40 minutes. Following that brief but parsimonious phase, it didn’t take long for me to revalue albums which got it over with in a shorter time: It’s a Shame about Ray (1992) by the Lemonheads, 13 tracks clocking in at a blistering 33 minutes, The Pixies, Bossanova (1990) 14 tracks in 39 minutes. These lissom, finely-tuned sprinters became exceptions, though, as lumbering fatties, sweating around the park, became the pop-music norm. Oasis’ Be Here Now (1997), was still there, much later; Catatonia were Equally Cursed and Blessed (1999)—yes, but how lengthily so …

It’s worth suggesting the future possibility of CD’s going the way of shellac or eight-track cartridge as a format that dies away: a change in CD hardware, possibly tied to computers, or another complete format shift. If so, the CD album may become marked off more strongly as a separate format. Who knows? Back in Sweden, Andreas’ answer to the embarras de richesse of lengthy CDs was only a button away:

I like the CD format for a whole bunch of reasons: I can program it, I can put it on random and pretend it’s a radio, it’s reasonably long lasting and I don’t have to get up every 20 minutes. In a sense the programming (read ‘deleting’) feature became essential only because of the CD itself, because it was the CD format which brought most of the dead time along.

This is sensible, and puts the emphasis of control of an album onto the listener. In a way, it takes the album back to the idea of the photograph album. It suggests a basic question: can one continue to speak of the CD album as a pre-programmed entity?

Having argued for the importance of the CD album as a form in its own right, I want immediately to undermine my claim by suggesting another, parallel background. As a principle: the CD album was produced against the imaginative background of the vinyl album and single. The invention of CD was in a sense more profound than the moment of shellac handing over to vinyl, since record players were still able to play the 78s. CD, like cassette, was a new form of ‘hardware’, and so the opportunity presented itself of reissue, suggesting, at its capitalist best, that record collectors buy second copies of records they already had. (I have De la Soul’s Three Feet High and Rising (1989) on vinyl, cassette, CD, and CD reissue with bonus tracks.) The additional time of the CD also enabled the recycling of back catalogue, snapshots of the whole lifetime of tracks: demos, out-takes, edits, mixes, B-sides, radio sessions, live performances, influences, cover versions. What this did was to create an overwhelming sense of ‘canon’: for a new band producing music in the early 1980s the ‘opposition’ tended simply to be the new music of the day, whereas a decade later, bands had to factor in a constant stream of ‘classic’ music from the past.

In terms of length, there was a counter-movement away from the idea of filling in the 74 minutes come what may, towards either an evocation of the vinyl sides, or an insistence that the material had reached a natural and shorter limit. There were some clunky examples. Wilco’s Being There of 1996 was a deliberate attempt to evoke the double album (the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street (1972) perhaps the precursor) with a ‘fake’ division of 36 and 40 minutes respectively. Masters of capitalist control, the Beatles preserved both red (1962-66) and blue (1967-70) retrospective compilations as double CDs to imitate their vinyl originals, even though the red one could easily have fit onto a single CD. Typical of a record fan, Elvis Costello issued in 1989 a compilation, Girls! Girls! Girls!, in three separate versions for each of the formats—vinyl, cassette, CD. As the reissue programmes proliferated, the critics’ choice list acquired new kudos as consumer guide. The lists compiled by Robert Christgau for the Village Voice had always served this purpose; in the UK, the NME’s occasional top 100, and their Xmas best of the year, seemed to be a different thing: critics exercising their elitist judgement consciously against the background of previous lists. For many years the NME’s Xmas list included ‘lest we forget’ charts of the ‘winner’ for the previous ten years. These lists were consistently compiled by critics: there’s a big difference in charts which include votes by artists or—something which the NME in those days might well have found ludicrous—readers. There was a charming tradition of leaving the 100th position in ‘best ever’ lists to a reader, though the decision depended really on the reader’s ability to write well and the NME’s sense that they’d made the right choice: it was anything but the most popular vote. One sensed the sign of change by the time of Mojo’s top 100 of 1995, with the whole edition built around the chart; and with the last NME top 100 in 2003 the chart had become little other than another, predictable consumer guide. Other indicators of the change from a critic-led to consumer-led view of value at this period would be found in the increasing presence of evaluative summary indicators, stars, and numbers out of ten.

During the 1990s the burden of the past weighed heavily on young bands, and forming links with the past became a feature. Whereas at various points in British pop music history, what had dominated was an emphasis on modernity, innovation, novelty, and pop savvy, at this time genuinely musical tributes and demonstrated fealties seemed to be the order of the day. Where the Beatles, Stones, and Kinks had adopted American models only as a distancing element from the pop music of the present, where the Clash began their early records reviewing the state of pop music only to deride it, where the Jesus and Mary Chain set out deliberately to usurp notions of technical proficiency, all three moments overlaid with a sense of generational fissure, in the 1990s bands seemed ready and even proud to reach out to the earlier generations in a new and generously inclusive way. Suede were photographed alongside Bowie, Oasis seemed to take bearings strictly from the Beatles, Damon Albarn of Blur sang along with Ray Davies of the Kinks, and, with great wit, Elastica made crafty allusions to and inclusions with precursors in punk (Stranglers, Wire, Clash, Fall). CD albums may have had all the time in the world, but CD also kept vinyl’s track record hauntingly in view.

Philip Larkin, asked by John Haffenden whether he takes care in ordering the poems in a collection:

Yes, great care. I treat them like a music-hall bill: you know, contrast, difference in length, the comic, the Irish tenor, bring on the girls. I think ‘Lines in Young Lady’s Photograph Album’ is a good opener, for instance; easy to understand, variety of mood, pretty end. The last one is chosen for its uplift quality, to leave the impression that you’re more serious than the reader had thought. (Interview with John Haffenden (1981)

If the CD album was still produced, invented even, against the background of the vinyl model, what did those models sound like? The basic issue, we’ve already seen, is unity against diversity, album as carefully-ordered or conceptual unity against the principle of compilation (the photograph album).

Here’s the classic vinyl album. Ten or twelve tracks seem to have been the going rate, five or six on each side. The fact that the side would need to be changed is crucial of course, meaning that both sides had to contain their own sense of progression. Double and triple albums simply multiplied this assumption—each single record had to present two track runs, one per side.

One obvious principle is the ‘bookend’, the balanced opening and ending. My favourite example is Street Legal (1978) by Bob Dylan which, whatever one made of its content, seemed a satisfying, format-derived shape. Not only does it fade out at the end, it fades in at the start, and both framing tracks are weighty which, in Dylan’s case, often means many-versed. If ever a guitar solo earned its place, it’s the one at the very end of this album. Side one in turn ended with a good slow song, ending with a big chord; while side two started with wake-up call on drums. Dylan also played with the side turn on Planet Waves (1974), opening side two with a ‘cover’ of the song at the end of side one. If endings turn out to be a problem for albums, then this is nothing new, the finale having been at issue in the multi-movement classical-romantic work (quartet, sonata, symphony), trapped between laboured gravity and dismissive lightness.

Within the side, the ‘run’ or flow of tracks arrange themselves by the relation of fast to slow, loud to soft, shorter to longer, either within one style or between different styles. The positioning of a hit single, a slow song, or a comedy song, is important. The array and arrangement of musical forms also play their part: songs that proceed verse by verse, songs with choruses, songs with middle eights, drama songs. So, in addition to great albums, one could make a case out for great sides or great runs on otherwise flawed albums. The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion (1992), by the Black Crowes, which I had on cassette, has a first side so perfect I’m pretty sure I’ve never heard the second side, preferring to wind the tape back for fear of disappointment. Greatest side ever: side one of The Velvet Underground and Nico (1967)?

By getting rid of the side change, the CD album, arguably, placed a new emphasis on precisely the middle of the album, in addition to openings and endings. Another thing I remember with the early CD was the bunching together of singles towards the start of the album, as though the assumption was made that the album might be switched off soon after starting.

These are collections where there really is no reason to attend to the organization of sound, since another principle of organization takes precedence. CD2 of British Bird Sounds on CD (British Library National Sound Archive, 1992) begins with the woodlark not because it’s a killer birdsong, but because the collection is carefully following the ornithological order established by Voous. Sound effect records, library records come into this category. CD reissue programmes brought this approach back to attention, with the inclusion of acres of demo material: the Pet Sounds box set, a 4 CD version of the Beach Boys album, clearly included material for its existence rather than necessarily because it made for an interesting record.

In the early days of CD, Brian Eno, characteristically, on the album Nerve Net (1992), included two versions of the one track, ‘Web’, and ‘Decentre’ as appendix, because he didn’t want to have to decide whether to include them or not: it would be for the listener to decide. CD allowed for a more distracted listening. Rap albums tended to build in the distractions of listening, with skits, chats, statements, and other forms of sonic disturbance between the set tracks.

The slow burner opening, the big kick-in, the satisfying run, and the problem of how to end. David Byrne’s Luaka Bop compilations struck me as masterly, in that they made me listen to songs in a language I didn’t understand without losing interest. Compilations of labels or periods can sometimes seem like a distinguished professorial chair, where the standard being set, as the tracks go by, is so high that not reaching it is going to be very noticeable. As though to confirm his position for my generation of listeners in Britain, John Peel’s DJ set for the Fabric label (2002) encapsulates that peculiar mixture of punk rock, reggae, pop music, and dance music (and interest in soccer): its 70 minutes go by very quickly indeed.

Greatest hits compilations have a basic ‘aesthetic’ question, which is whether to be arranged chronologically or simply as a good compilation. The placing of the one or two big hits is an interesting thing to observe. Conversely, for those whose number of hits (or at least of singles issued) amount to a time greater than that available to the format (Elton John always seems to reach a point of format excess), the choice of what to include or leave out is again interesting.

These have to follow the show, which will tend to save its best moments till later. The live double album was a staple diet of the 1970s and is still to be found on CD (Oasis, Dixie Chicks, Steve Earle). Radiohead’s own live mini-album is more of a compilation.

The idea of giving the album a unified character of some kind across its various tracks makes sense, not least after a band or singer has recorded the first record which brings together already-existing, tried-and-tested, disparate songs. However, the question of where the unified album gets its bearings from is an interesting one, and depends on the historical background evoked. If we talk of ‘pop music’ as a self-contained world, the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) functioned as the archetype of the unified record. In the 1970s, when Elton John and Bernie Taupin did the extended Goodbye Yellow Brick Road (1973) album, or the autobiographical Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy (1975), it would have been Sgt Pepper, or the interlinked second side of Abbey Road (1969), which would have exercised the rock critic’s imagination as comparison. The rock opera—the Who’s Tommy (1969) and Jesus Christ Superstar (1970), for instance—seemed to emerge from the interlinked double album as much as from the theatre. Some sense of conceptual unity seemed to become a key element of progressive rock albums.

Outside pop’s self-contained world, however, other models might be found, in the song-cycle of classical music, and the sequence of poems, depending on whether one chooses to come at it from the point of view of music or words. The novel, the drama, or the narrative film, may also offer correspondences: looser amalgams of stories and scenes held together by one ongoing narrative. Elvis Costello’s Imperial Bedroom (1982) always struck me as a sort of novel depicting— guess what?—a relationship, even though Costello doesn’t seem to have made this explicit. The first, interlinked side of Lloyd Cole’s fine Don’t Get Weird on Me, Baby (1991) seemed to present unity from the perspective of a novelist manque, complemented rather than established by its music’s evocation of the world of Jimmy Webb’s songs for Glen Campbell. The other word-based source would of course lie in drama—the individual songs contributing to an ongoing narrative thread, and these follow their own history in pop music, separate from but also deeply connected to, the history of musical theatre itself. It’s possible to get frustrated about this aspect of the album, by positing unity or collection or correspondence as an inherently better thing; here’s one of the great songwriters, Jimmy Webb:

I can see a lot of things to be done with songs that haven’t been done with them. We haven’t seen a lot of songs written in free verse. We haven’t seen a lot of songs written in a chain of consciousness form with no particular verses, choruses or bridges. Aside from the thing Van Dyke Parks wrote a few years ago (Song Cycle) and a few others, there have been very few legitimate song cycles written in the pop field.

Here, ‘legitimate’ is working too hard. If anything, in the pop world, there were far too many half-baked attempts at the unified album. The distinction perhaps to be made, familiar from the song-cycles of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, is between thematic and musical unity. The concept album could be seen as ‘merely’ held together by a narrative, thematic, dramatic thread, while the earlier song cycle, Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte, Schubert’s Winterreise, or Schumann’s Frauenliebe und Leben could include musical markers to point up connections: the return of opening material, for instance, melodic links between songs, a consciously-conceived arrangement of keys. Dyke Parks’ Song Cycle (1967) isn’t much other than a collection of songs informed by the availability of styles that characterized the West Coast album of the day: interestingly orchestrated, and with words that did indeed bear some of the scars of literary modernism. But it’s no more perceptibly cyclic in the Schumann sense than Sgt Pepper—Jimmy Webb is possibly deceived by Song Cycle’s title.

In evoking the song cycle, a distinction needs to be made between ‘song writing’ as we’ve come to understand it, and ‘text setting’, a very different practice and tradition. In the German Lied, French mélodie, or English songs such as those of Gerald Finzi or Benjamin Britten, the words are given as poetry, and in a sense the whole point of the ‘setting’ is to make the words into music, so that the emphasis is clearly still on the musical manifestation of words already given. With the invented song, attention is more equally divided between the music and ‘what the song is about’, which is anybody’s guess. It also gives the band, their songwriter(s), or at least their word-controller, the opportunity to string together the thematic content of a group of songs: why, it would be peculiar if they were to be constantly and deliberately separated. (As an aside, the Grateful Dead were the famous example of word-controller Robert Hunter being outside the group, as indeed were the Beach Boys’ albums Pet Sounds and Smile, the latter with words by Dyke Parks himself.)

Judy Collins, In My Life (1967), The Beatles’ albums after Revolver (1966), Randy Newman’s first album (1968). In their own way, Oasis weren’t so far from this on their first two albums. The rock album became so much a ‘norm’, where the band is playing all of the time, that it’s possible to forget about the possibility of the entirely arranged album. The Judy Collins album is terrific: a reminder of a time when records could bring together Randy Newman and John Lennon with Peter Weiss and Bertolt Brecht.

Any attentive album fan would do well to keep a close watch on portraits, artwork, graphics, logos, the presence or absence of words, listings, copyright statements, and acknowledgments. However disunited the material of the album, it is always possible for its visual support (or even just the title) to strongly suggest conceptual unity.

Another way in which vinyl continues to cast its shadow over the CD is the survival of the single, and we need to consider its history a little here. Back in 1948, during the ‘battle of speeds’, the 45 rpm single seems to have appeared partly by chance; there was even a suggestion of multiple singles, crashing down one after the other, to create an equivalent to the time continuity of the LP. However, the association of 45 rpm single record and song, so lovingly celebrated in a book like Dave Marsh’s The Heart of Rock and Soul, became something deep and ingrained. To my baby-boomer generation, ‘song’ and ‘record’ became inextricable. This takes us back to Keir Keightley’s description of the album as more than ‘merely a collection of songs’: there’s something quite fundamental here about the nature of the song, as opposed to musical material that isn’t a song. As the reader will by now have guessed, I tend to see this to a large extent as a matter of the occupation of time, so that songs form an alliance in brevity with some other musical forms: Beethoven’s bagatelle, the character piece, the modernist Stück, the miniature, the compressed version of operas found in their overtures or preludes. There aren’t really so many forms of music that are intrinsically lengthy: in classical-romantic music the sonata-form movement, with its tonal opposition, extensive harmonic and motivic development, became a formal ‘template’ that could consciously be expanded by a composer such as Brahms; the continuous ‘stream of consciousness’ of the Wagnerian opera; composed pieces of musical modernism that, rightly or wrongly, assume listener concentration. For the latter, Joyce is the literary equivalent (with Wagner somewhere in his background, too), describing famously in Finnegans Wake ‘an ideal reader suffering an ideal insomnia’.

With the invention of CD, any format-derived necessity to link track with length effectively vanished, and the single seemed to become, more frankly, something which it had been for some time: a marketing device to announce the appearance of an album, a sort of trailer for the film. Nevertheless, that deep liaison between song and single format is still something that continues to haunt the CD single. In fact, the main element of the single, song, or track, which then becomes notable is precisely when it gets longer, and we can distinguish some models, and in each case suggest a typical example.

Example: ‘Scenes from an Italian Restaurant’ (Billy Joel, 1977). Bruce Springsteen always seemed on the verge of a long drama song at the time of Born to Run (1975); Shadow Morton’s productions of the Shangri-Las perhaps represent the pop origin of the drama track. Comedy singles shouldn’t be under-estimated, either: famous old examples like ‘Ying Tong Song’ by The Goons (1956) or ‘Banana Boat’ by Stan Freberg(c.l957) occupy a compressed time frame in remarkable ways.

Example: ‘American Pie’ (Don McLean, 1971). The ballad (to mean multiply-versed narrative rather than record for slow dancing) is the progenitor, but there’s much skill in being able to spin the rhymes and verses and remain interesting. Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell have great examples, though Bob Dylan is the master of prolixity: the collection Greatest Hits Volume Three (1994) opens with four examples, any one of which might have been a ‘lifetime best’ for most songwriters. My vinyl single of McLean’s ‘American Pie’ preserves a split in the middle of the song: indeed, even now as I listen to the track on CD, I’m still tempted to get up at that point in the song to turn the record ‘round.

Example: ‘MacArthur Park’ (Jimmy Webb/Richard Harris). See Webb’s model of this form in his excellent book Tunesmith. Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ (1975), perhaps the favourite among long tracks, is a mixture of the drama track in its rapid operatic section and the slow ballad at start and end.

Example: ‘Hey Jude’ (The Beatles, 1968). ‘Hey Jude’ was apparently extended to its final length (7’20”) simply in order to ‘beat’ ‘MacArthur Park’ as the record for long single. But it’s simply a slow song, with a fade-out which does really very little, the Beatles by then popular enough for such indulgence to be tolerated and celebrated. ‘Hey Jude’ is the strong precursor of many CD tracks: an ordinary short-but-slow song with an extended ending. In soul music, a track could become longer by a repeated ending: Al Green’s ‘Let’s Stick Together’ (1972) takes over two minutes of repeated material to end (and then fade!), while Aretha Franklin’s cover of Paul Simon’s ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ (1971) takes two whole minutes to reach the start of the song.

Example: Manic Street Preachers, ‘If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next’ (1998). Like ‘Hey Jude’, the song is over with after two minutes and, as an equivalent of the fade in the Beatles single, there’s still over two minutes of aural wallpaper to go. This became the template for many individual tracks on the CD album.

CD singles are surely even less likely than the CD album to survive as a category: they really make little sense. In some ways they are a return to the EP, the ‘extended play’ format of the 1960s. The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour (1967) was originally and effectively a two-EP collection. The CD single did sometimes work more crisply and cogently than the albums they were intended to advertise: Oasis, in my opinion, were far better presented in this format than on the albums (at least after the first one). ‘D’You Know What I Mean?’ (1997) was followed on a CD single by two contrasting tracks and a rousing cover (of Bowie’s ‘Heroes’), a collection evocative of the album as miscellany.

Oh yes, OK Computer, remember that? What is it? I’d say it’s a CD album, and by that answer I mean a format that was prevalent during the time of its production and release. In the future, it may well be that the CD album has an endpoint as well as a start: it’s not dark yet for the CD album, but it does seem to be getting there, as downloading seems to emphasize afresh the principle of compilation over ‘set’ track order.

There are several ways in which OK Computer illustrates the discussion so far:

• At 53-54 minutes it lasts longer than vinyl records do in general, and naturally without side break. It’s hard to generalize about vinyl length overall: set next to Bob Dylan records, for instance, OK Computer lasts twice as long as Nashville Skyline, but not as long as Desire. But they, of course, include the side break.

• The tracks are generally long and, in turn, evoke formal models of the long track.

• It has some sense of unity, suggested in its title and reinforced by its visual presentation. The progression of tracks does seem to have been considered. James Doheny: ‘we do know that Thom Yorke spent two weeks rearranging the album’s order on his Mini Disc’ (78). It would surely be surprising if this were not the case.

• Although a CD album, it’s worth pointing out that a vinyl version of OK Computer does exist, with four side divisions labelled ‘eeny’ (tracks 1-3), ‘meeny’ (4-6), ‘miney’ (7-10), and ‘mo’ (11-12). This balances the argument for random programming to a small extent. I don’t know of a cassette version with strictly two sides, though in reviewing the album for NME James Oldham described a ‘side two,’ which began with ‘Fitter Happier’. Random programming would undermine much of what’s to follow in this book, and that needs saying, but I assume generally that the order of tracks does matter.

• In ‘Paranoid Android’, it contains a notably long track (and single). In fact, three singles were released: (in order) ‘Paranoid Android’, ‘Karma Police,’ and ‘No Surprises’. ‘Lucky’ had appeared in 1995 among the singles from The Bends as part of a charity record for War Child.

• During its brief history, the album has appeared in several ‘best of lists, many of which include it alongside earlier, vinyl albums.

Hopefully the remainder of the book will help bring out these features. The last one is something which lies outside the album, and some of the conceptual unity needs dealing with separately. But in general terms, the points can be made by referring to individual tracks and to the album as a whole.

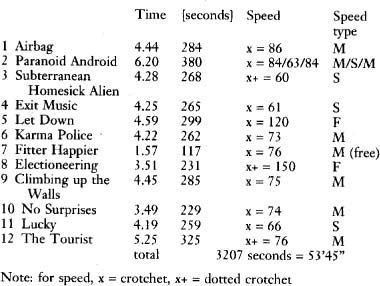

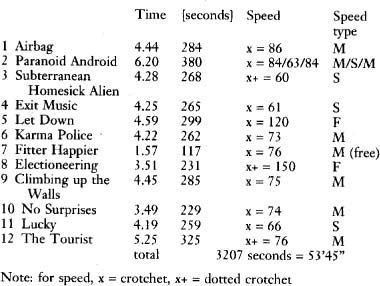

To start with, here’s a breakdown of the album into its constituent tracks to demonstrate the length of track. It’s hard to generalize about the ‘norm’ for the length of records—as a quick comparison, ‘All Shook Up’ by Elvis comes in just under two minutes, and the ‘three-minute single’ became a standard phrase. The third of Cauty and Drummond’s four golden rules for a hit single is that it ‘must be no longer than three minutes and thirty seconds (just under three minutes and twenty seconds is preferable)’.

Speed type—this translates the speed into three types, slow, medium, fast. ‘Let Down’ is fast but doesn’t necessarily sound fast: the pulse of the vocal line proceeds at double-speed—minims in the sheet music. ‘Fitter Happier’ also sounds looser and freer than the speed indication suggests. The speed column isn’t as technical as it may seem, the numbers indicating beats per minute. The slow section of ‘Paranoid Android’ is just over sixty beats per minute, so that looking at the second hand of the watch will show its pace. ‘Let Down’ is two to the second, and again the watch will show how lively that is. ‘Electioneering’ is five beats per two seconds. Slower-paced songs fill the time easier simply by working through their verses; additional material will be found in the medium and quickly-paced songs.

Thus, in simple quantitative terms the tracks on OK Computer average 4.27 each; however, if the notably short track seven is removed, the average length is 4.40. This is longer than Radiohead’s previous album The Bends, where the average length of tracks was 4.03. That may not seem a big deal, but in music in general, the world of the pop song in particular, a minute is a very long time indeed.

Next, and in order to start approaching each track in turn, I now want to focus in on individual track length, speed and, in so doing, the relation of song to record. One thing all pieces of music do is start and end, and the CD clock enabled us to focus, probably as never quite before, on the length of tracks: appearing in 1995, Ian MacDonald’s Revolution in the Head was surely led to its detail by the digital clock. Speeds tend to be consistent once a track is under way, and this is true of pieces of music in general: ‘Paranoid Android’ and ‘Electioneering’ are exceptions. The published sheet music supplies these indications: I sometimes disagree slightly with them, but I’d be more inclined to believe the score than me. The question: how is the length of tracks achieved? We can start to divide each track up into its constituent elements: here, I take the number of bars as a consistent proportional device. One could equally take clock time as a guide, but counting bars is easier done: anyone who can dance can follow beats and bars.

For the complicated question of the role of the voice, I’ve then observed the relation between ‘wordy’ and ‘wordless’ sections, again as bar numbers. (Sadly, the word ‘wordful’ does not exist.) This is a way of gauging how much each track conveys its information through language and ideas, and how much is left to music without words. It’s also an interesting way of considering the changing function of the voice: the voice as carrier of the words, and the voice as analogous to a particular kind of instrument. Backing voices add to this issue.

The following is dense and technical at least in that it uses numbers, and the reader may wish to skip to the end of the chapter. However, the more the tracks are listened to, the clearer these divisions will appear: they are simply representations of the time taken by each track, what happens, how the music goes. Words are included as indicators. This section represents a tribute to the album, proof of effort; we’re then ‘more free’ to become informed critics. Understanding does take time but, hey, what else are you doing for the next few minutes, anyway?

Airbag (Information from first chart: 4.44/284/x = 86

Intro: 9 (preceded by one-note upbeat)

Verse: 12 (6+6)—’In the next world war …’

’Chorus’: 6—’In an interstellar…’

Link: 5

Verse 2: 12 (6+6)—’In a deep deep sleep’

Chorus: 6—as before

Break; 2 (6+6)

Chorus: 6+6—as before

Break: 14 (4+10)

Coda: 10, followed by one bar of single beats

wordy: 48, wordless: 51

Paranoid Android (6.20/380/x = 84/63/84)

To get the relation between sections about right, assume one bar

to be four beats at both speeds.

Section A (G minor)—160 beats (wordy: 136, wordless: 24)

Intro: 6 (2+2+2)—24 beats

Verse 1: 4+2+4—40 beats—‘Please would you stop … ’

Refrain: 4+3—28 beats—‘What’s there?’

Verse 2: 4+2+4—40 beats—‘When I am king …’

Refrain: 4+3—28 beats—as before

Modulation to:

Section B (same speed) (A minor/C major)—130 beats (wordy: 32, wordless: 98)

Break: 4+4* (4* = 7 beats (NB)+7+7+8)—16 beats plus 14.5 = 30.5

Verse 3 and 4: 4+4*; 4+4* (note that the 4* sections are largely wordless)—61 beats—‘Ambition makes … ’

Break: 4+4*^30.5 beats

Pause: 2—8 beats

Modulation to:

Section C (slower speed) (C minor/D minor)—128 beats (slower) Middle section (slower): 4 x (4x8 crotchet beats). (Note that the first of these is wordless)—‘Rain down’

Modulation again to:

Section D (B return) (A minor/C major)—61 beats (speed one) (all wordless)

Break: 4+4*, 4+4* (all wordless)—61 beats

Speed one (351 beats) wordy: 168, wordless: 183

Speed two (128 beats) wordy: 96, wordless: 32

totals (reducing speed difference): wordy: 264, wordless: 215

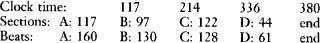

In terms of time, all timings in seconds, the sections work out as:

Subterranean Homesick Alien (4.28/268/x = 60)

Intro: 4+8 (4+4)

Verse: 4+4 (vocal) +4; 4+4(vocal)+4—‘The breath of the morning …’

Chorus: 4+4+2—‘uptight’

Link: 4+4 (as at intro)

Verse 2: 4+4 (vocal)+4; 4+5 (note extension)+4+4 (version of intro)—‘I wish that they’d sweep …’

Chorus: 4+4+4 (note additional repeat)+2—as before

Coda: 4+4+3 (+pause—opening phrase as ending)

wordy: 76, wordless: 32

Intro: 6

Verse 1 and 2: 8+8—’Wake from your sleep …’

Chorus: 5 (2.5+2.5)+l+5 (2.5+2.5)+2—’Breathe …’

Verse 3: 8—‘Sing us a song …’

Bridge: 4+4—’And you can laugh …’

Verse 4/Coda: 8+4+4 (repeated end phrases)—‘And now we are one…’

wordy: throughout

Let Down (4.59/299/x = 120)

Intro: 10. This is a series of five-quaver loops that follow the pattern: abcbabcbabcb, and so on. Because they’re multiples of five, the main accent of the four-beat (eight-quaver beats) varies, coinciding every five bars (5x8 = 40). However, the repeated ‘b’ phrases bring further melodic coincidences. In listening, you can achieve Zen Buddhist levels of concentration, by counting fives (one, two, three, four, five) with the guitar notes. Or the phrase, ‘I love Tony Blair’ or ‘I hate Tony Blair’ (or any five-syllable phrase with a masculine ending), and hear the ‘Blair’ word move around. The systems game is over by the end of the verse.

Verse 1: 8+8—‘Transport, motorways …’

Chorus: 3+3+3—‘Let down and hanging …’

Link: 4

Verse 2: 8+8—‘Shell smashed …’

Chorus: 3+3+3—as before Link: 4+4+4+4

Chorus: 4+4+7 (1+6)—as before

Verse 3: 8+8—‘You know, you know where …’

Chorus: 3+3+3—as before

Coda: 7

wordy: 90, wordless: 37

Karma Police 4.22/262/x = 73)

Intro: 8

Verse 1 and 2: 8+8—‘Karma police …’

Chorus: 8—‘This is what you get… ’

Verse 3: 8—‘Karma police …’

Chorus: 8—as before. Modulation to:

Section B: 4+4—‘For a minute there …’

voice: 4+4, 4+4, 4 (pause)—as before

wordy: 40, wordless: 40 (includes 8 intro)

Fitter Happier (1.57/117/x = 76)

Spoken, and wordy throughout. For music-word correspondence, see chapter two.

The almost-two minutes of ‘Fitter Happier’ get filled in this way:

l”–3”: voice alone

3”–18”: voice plus sound effects

18”–53”: piano—B flat minor

53”–1 ‘38”: piano—G minor

1’38”: back to B flat minor

1’45”: piano drops out

1’50”: voice drops out, sounds effects alone to:

1’ ‘57”: end

Electioneering (3.51/231/x = 150)

Thirteen seconds sounds effect/open fifth to:

Intro: 4+4+4

Verses 1 and 2: 4+4/4+4/4—‘I will stop…’

Chorus: 4+4/4+4—‘When I go forwards …’

Link: 4+4

Verses 3 and 4: 4+4/4+4/4—‘Riot shields…’

Chorus: 4+4/4+4—as before

Break: 5 (slower)—I count this (just clapping away in time) as nearly II bars of the faster tempo. Back to first speed for:

4+4+4+4

2+2+2+2

4+4+4+1

wordy: 72, wordless: 65 (includes 5 at slower pace: by my reckoning it comes to 71)

Climbing up the Wails (4.45/285/x = 75)

Eleven seconds sound effect opening

Intro: 4+4 (2+2+2+2)

Verses 1 and 2: 4+4+1; 4+4—‘I am the key …’

Chorus: 4+4—‘Either way you turn …’ (the second of these largely wordless)

Verses 3 and 4: 4+4+1; 4+4—‘It’s always best when the light…’

Chorus: 4+2—as before (note the compression)

Break: (4+4)+4

Voice: (2+2)+(2+2) (scream)

Coda: over 35 seconds, falling into three parts: the chord itself (E minor), the chord with its bass removed, and then the cluster of notes start to appear, first with sound effects added, and then as strings alone.

wordy: 56, wordless: 28 plus the big coda and the intro

No Surprises (3.49/229/x = 74)

Intro: 4+4

Verses: 4+4, 4+4—‘A heart that’s full up …’

Verse-chorus: 4+2+2+2—‘I’ll take a quiet … No alarms …’

Intro and voice: 4

Verse-chorus: 4+2+2+2+2 (intro)—‘This is my final fit… No alarms …’

Break: 4+2

Verse-chorus: 4+2+2+2 ‘Such a pretty house … No alarms …’

Intro: 4+1 (rallentando and pause)

wordy: 48, wordless: 23 (plus pause)

Lucky (4.19/259/x = 66)

20 second sound effect introduction

Verses 1 and 2: 3.5+3.5 (beats: 4+6+4, 6+4+4); 3.5+3.5—‘I’m on a roll

Chorus: 6+1.5 (6 beats)—‘Pull me out of the aircrash…’

Link: 4 (2+2)

Verses 3 and 4: 3.5+3.5 (beats: 4+6+4, 6+4+4); 3.5+3.5—‘The head of state …’

Chorus: 6+1.5 (6 beats)—as before

Break: 4+4; 2; 6+2 (voice returns at end)

wordy: 45 wordless: 20

The Tourist (5.25/325/x = 76)

Intro: 4+2+3*+4 (* note that the third bar consists of four beats)

Verses 1 and 2: 4+2+3*+4; 4+2+3*+4—‘It barks at no-one …’

Chorus: 2+2+2; 2+2+2—‘Hey, man, slow …’

Link: 2+2+2

Verses 3 and 4: 4+2+3*+4; 4+2+3*+4—‘Sometimes I get overcharged …’

Chorus: 2+2+2; 2+2+2—as before

Chorus: 2+2+2; 2+2+2—as before

Coda: 4+2+x

wordy: 88, wordless: 43+1 (44)

Radiohead was by 1997 already an established rock band, ascending into an elite which included the two 1980s survivors, U2 and REM. In the British context, for some reason, the band had avoided being associated with Britpop, such that in 1997 itself, OK Computer appeared relatively quietly, while much immediate attention was devoted to Oasis as well as to Blur, Elastica, Pulp, Paul Weller, and Ocean Colour Scene. The Bends was three years old, and dating very well indeed; while further back, the memory of ‘Creep’ and the first album Pablo Honey (1993) was especially important outside the UK. These things are never clear at the time, and on release OK Computer might have sent Radiohead backwards. From the chart success of ‘Paranoid Android’ and the album’s critical reception onwards, however, that just didn’t happen. If there was something musically, and music-historically, unusual about Radiohead, it lay in a line-up which included three full-on guitarists. After OK Computer, the strictness of the line-up gave way to more experiment in instrumental and sound producing roles. Doheny includes clear summaries of how their records fared in the US and UK charts (OK Computer number 21 in the US, 1 in the UK). From the start, Radiohead has been on the Parlophone division of EMI, managed from 1950 by George Martin and thus home to the Beatles in Britain. By the time of OK Computer, it included Queen and Tina Turner as well as Supergrass and the Divine Comedy. A Radio-heady footnote: Dave Laing tells how the label, originally the German Parlophon, was during World War One ‘confiscated in Britain as enemy property and ceased to exist’.

Simon Frith rightly insists (in Performing Rites) on the circulation of records (as opposed to music per se) as the foundation of pop-music influence, and this is naturally true of Radiohead. Funnily enough, in Jonathan Greenwood, they have someone who’s influenced in the old style, by having played music, Messiaen especially, as a member of a youth orchestra. But otherwise it’s records all the way, with books and films behind some of the words and ideas. An early questionnaire for Melody Maker in 1993 (reprinted in the NME Originals compilation of 2003) gathered together favourite records and bands. Influence is too big a topic to go into here, but I’d be inclined to emphasize early influences, partly because later things have less time to be assimilated and, well, flattery and favours and careers understandably come into play: now, it wouldn’t be so surprising if REM or Bjork or PJ Harvey got added to Thom Yorke’s list, Asian Dub Foundation to Ed O’Brien’s, and so on. Here were the early favourite albums and bands:

Colin Greenwood: Joy Division, Unknown Pleasures; Nick Drake, Bryter Layter; Miles Davis, Kind of Blue, and In a Silent Way; Gram Parsons and The Fallen Angels, Live 1973; Sly and the Family Stone Greatest Hits; Parliament, Rhenium

Bands: American Music Club, kd lang, David Gray, Strangelove

Jonathan Greenwood: Art Blakey, Moanin’; Magazine, The Correct Use of Soap; Messiaen, Turangalî la Symphony; Can, Tago Mago; Talking Heads, The Name of this Band is Talking Heads

Bands: Moonshake, Strangelove, Sonic Youth, Human Torches (Oxford band), Boo Radleys, The Fall

Ed O’Brien: Bob Dylan, Blood on the Tracks; REM, Murmur; Glen Campbell, Gentle on My Mind

Bands: Strangelove, Kitchens of Distinction, Sonic Youth

Phil Selway: Barrett Strong, ‘Money’; Joy Division, ‘Atmosphere’; The Ruts, In a Rut; Nick Drake, Five Leaves Left; The Beat, Wha’ppen; Richard Thompson, ‘1952 Vincent Black Lightning’; Blue Bossa (a Blue Note compilation)

Bands: CNN, A House, Cranberries, Moonshake, Strangelove

Thorn Yorke: Tim Buckley, Happy Sad; Elvis Costello and the Attractions, Blood and Chocolate; Can, Tago Mago; REM, Life’s Rich Pageant; Syd Barrett, The Madcap Laughs; Japan, Quiet Life

Bands: Th’ Faith Healers, Underground Lovers, Swell, David Gray, Stereolab

The named records seem more interesting, while the favourite bands seem to reflect perhaps more on live performances seen recently at the time of the article (as well as fulsome tribute to the band Strangelove). Other influences to emphasize are, for guitar style and principle of ‘sonic assault’, John McGeoch (Magazine, Siouxie and the Banshees); and the Pixies (Joey Santiago), for sure—presumably the band were still to run into them; Morrissey and REM’s Michael Stipe for songwriting principles; the later Beatles perhaps—scope, studio experimentation. It’s possible to see some elements of progressive rock in Radiohead: conceptually-unified albums (maybe), longer tracks, elements of the musical material, and instrumental virtuosity. After OK Computer, a lot of fresh material enters the picture: a splendid short article in Q magazine offers a guide (no. 179, August 2001, p. 97)

The purpose of the discussion so far has been to set a context for the Radiohead album in which recording technology affects the form of the musical material. We’ve gone some way into the material itself, particularly the way the tracks occupy the time available. There’s another aspect, more distant admittedly, about the nature of a ‘classic’ album which I’ve raised but not really engaged with: that aspect will return in chapter three. Now comes the enjoyable part, however: time to switch on the CD-playing machine, settle back, and listen to OK Compute.