We need to take into account a key conceptual distinction. On the one hand, there is the empirical spectator whose interpretation of film will be determined by all manner of extraneous factors like personal biography, class origins, previous viewing experience, the variables of conditions of reception, etc. On the other hand, the abstract notion of a ‘subject-position’, which could be defined as the way in which a film solicits, demands even, a certain closely circumscribed reading from a viewer by means of its own formal operations. This distinction seems fruitful, inasmuch as it accepts that different individuals can interpret a text in different ways, while insisting that the text itself imposes definite limits on their room to manoeuvre. In other words, it promises a method which avoids the two extremes of an infinite pluralism which posits as many possible readings as there are readers, each equally legitimate, and an essentialism which asserts a single ‘true’ meaning.—-Sheila Johnston

I am rather inclined to believe, for myself, that my best poems are possibly those which evoke the greatest number and variety of interpretations surprising to myself. What do you think about this?—T. S. Eliot

In the best of songs there is always something about what it is to write a song without in any way doing away with the fact that it is about things other than the song.—Christopher Ricks

Film is difficult to explain because it’s easy to understand.—Christian Metz

Airbag

Paranoid Android

Like The Bends, OK Computer has a fine opening. ‘Airbag’ seduces and dazzles; it felt on first hearing, and still does, like a boxer coming out at the bell on full attack. The sequence of events is carefully presented: the opening guitar/cello line, decorated with small variants, and then the confused drums. The title itself has already suggested a peculiar theme, and maybe there’s something airy about the opening sound-scape, but eventually one realizes that the song is about the airbags that are fitted to cars as a safety device. That’s clever: how something which sounds vast and symphonic is actually going to be reduced to the tiny realist detail of cars and accidents. Paul Simon has spoken about the contrast between ‘ordinary’ and ‘enriched’ language as being a key element of pop songs, and that distinction may be working here. ‘Symphonic’ doesn’t seem wholly out of place, either, or at least an adjective evoking the sonata rather than the symphony, since the punctuating melodic line has a sombre character, as in the Italian musical indication grave, reminiscent of the cello part in a Brahms or Fauré sonata (the ‘brooding’ line of the first Brahms sonata rather than the ‘heroic’ line of the second). Of course, sonata parallels only go so far, since this is not music setting up a tonal conflict, and here the formal working-through is limited to repetitions and contrasting sections. The idea of the novelistic detail, the airbag, being the pretext for this epic sound, goes back to The Bends, and tracks like ‘Fake Plastic Trees’ and ‘My Iron Lung’: considerable distance separates the detail itself and its representation. ‘Airbag’ is notably non-wordy, with the two instrumental breaks occupying much time as well as the returning introductory material. One of the things which I think listeners home in on is the layering of the guitars and drums, and the latter may be where people hear Teo Macero’s production style for Miles Davis. Note that the bass part in particular leaves out a lot of space and is itself very ‘motivic’—little figures leaving more a rhythmic than a melodic mark, and where the music generally has an upbeat, the bass part comes in on the beat. The music itself is quite tight in terms of ‘motive’ as well with lots of little descending melodic figures, maybe a counterpart to the craggy ascents of the opening and closing ‘cello’ melody. An arrangement of the album for string quartet, discussed in the final chapter, reinforces this impression.

Thom Yorke’s voice when it appears evokes in my mind Matthew Arnold’s famous phrase in Culture and Anarchy (1869), sweetness and light. The phrase derives from Jonathan Swift’s Battle of the Books (1704): the spider’s efforts end merely in cobwebs, while the bee gives us sweetness as honey and light as wax. Aesop, as a character in the story, links the spider to the Moderns, the bee to the Ancients, and Arnold was keen to link that analogy to the one he saw between Philistines and people of culture devoted, famously, to ‘the best that has been thought and known in the world’. Arnold also regarded sweetness as corresponding to sensuous beauty, light to intelligence. Thom Yorke’s voice creates the most remarkable sense of sweetness, palpably so, while the songs and their words correspond to a particular intelligence. In ‘pop music’, as a self-contained world, it would be hard to find the combination quite so well or extremely matched. Jackie Wilson may have the sweetest of voices, and gets the sweetest feeling, but the songs are pop songs, period. Donald Fagen may be the wittiest of songwriters but his voice didn’t descend from the angels. No, Thom Yorke is there with people like Morrissey (possibly), Joni Mitchell (for sure), Michael Stipe (possibly) and, to join this club, the voice has to be, so to speak, genetically prepared (Buckley père et fils, Houston mère et fille), possibly in the future by an ok computer, but then life has to intervene so that the song-writer ends up one of the ones with ‘something to say’. The great trick of pop music, the blues, has been to allow duff singers, strictly speaking—Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Neil Young, Patti Smith, Johnny Rotten, pretty much everyone—the chance to ‘sing’ in the sense of ‘doing remarkable things with the voice’ (the phrase belongs I think to Christopher Ricks, as said of Bob Dylan). Thom Yorke’s voice has its distinct ranges, highs and lows, but it’s clearly the high one which does the damage: a white-church voice redolent either of choirboys or, surprisingly enough, Art Garfunkel. Lower registers are going to be used for prose detail, confessions, bitterness; when the upper register appears there may as well be something worth going there for, since its height is going to affect the thing decisively.

So ‘Airbag’ is an agenda-setter for the album to follow: the voice, words, noise breaks, guitar solos, carefully positioned ‘motivic’ bass and drums, the details. ‘Paranoid Android’ follows, taking its place among notably long songs. The Radiohead contribution is a firmly delineated four-part form, with a slower third section and a curtailed coda. The diagram gives detail of overall proportions of the track, genuinely large in scale, extended in form, and including some complicated detail. The first two sections preserve the same speed but differ in rhythmic character, and the return of the second section at the end gives a satisfying sense of the first section as a big slab of material, the second section’s material wrapping itself around the third, slow section. (Early versions of ‘Paranoid Android’ included the return of the first section as coda.) The second section is characterized rhythmically by a numerical sequence in which the last ‘number’, eight, marks off an unusual sequence of three times seven. Playing this live night after night must feel like the gym: skipping rope, perhaps.

In musical content, ‘Paranoid Android’ perhaps already seems to bear its gothic aspect rather heavily—the figure at the start of the second section most responsible, I think. It’s rescued by the marvellous ugliness of ambition and the ‘screaming Gucci little piggie’, sure to annoy us at least until we continue to understand the evocations of the label ‘Gucci’ which, hopefully, won’t be for too long. There are some regal fantasies (monarchs: what can you do with them?), chucking someone at a wall and ordering their decapitation. Meanwhile, back at the hearth, the domestic heart of the record, the character of the song can’t sleep (don’t we all?) and seems unduly bothered by someone not remembering his name (don’t we all?). ‘Unborn chicken voices’ are close enough to unborn children’s voices: God loves his chicken, yes? Nerds worldwide are sure to point out the derivation of the title in Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

The slow interlude depicts rain of biblical proportion and is helpfully reinforced in a last run-through where the words return to good, dependable nastiness, yuppies thrown out of a bar and throwing up. The chord sequence progresses nicely, but has to lurch itself back to its starting-point, having modulated up a tone. Ordinarily, the chord sequence would sound seedy, rather like something by the band Portishead, and the vocal arrangement helps a lot. Obsessives might note the similarity between the phrase at ‘from a great height’ with the second subject of the Hebrides Overture of Mendelssohn, with possibly some deep ‘watery’ link—calm sea and prosperous voyage. My guess, though, is that it’s a track that will date rapidly, though brilliant at the time: few will forget the thrill of observing a seven-minute Radiohead track at number three in the British pop charts. Certainly, for the album, ‘Paranoid Android’ really sets out the terrain: ‘Beat this!’, it seems to say, not least to bands for whom such longeurs and details and determined ambition would be a fantasy at most.

Magnus Carlsson’s video animation for ‘Paranoid Android’ would be a good set text for the question, what is the relation between music and film? On the face of it there seems to be very little—the film’s cuts seem not strictly to correspond to the record (one exception is at ‘You don’t remember’, in the record at 2’42”). However, there are smaller correspondences, and the pace of the film interestingly seems to reflect the sound as heard. Naturally, the music imposes its own shape upon the film. In mood, too, the adventures of the cartoon protagonists seem to match the music, notably at the ‘Rain down’ section with strange depictions of urban anomie, risk-taking, suicide, and limbs being chopped off (suggested by the line, ‘off with his head’?). It’s a film of half correspondences, half suggestions, half certainties: the R on the character’s cap seems to be that of Radiohead, while the prominent fish belongs to the film (suggested by the rainy water of the slow section?).

Subterranean Homesick Alien

Exit Music (for a Film)

‘Paranoid Android’ is a hard act to follow, and there are three ways on record of so doing. The two versions of its CD single format are a bit hesitant. The first version follows it with a track called ‘Polyethylene’ in two distinct sections, the first a descending chord progression which was to resurface after a fashion as ‘Knives Out’ on Amnesiac. ‘Polyethylene’ is in turn followed by ‘Pearly’, a songy song: minor key, big vocals, and a nice bridge section. This is a much bigger and more Radiohead-ish track, a top B-side, but run through verse-by-verse, maybe a track that was deemed not to be heading anywhere. A Homer Simpson voice says ‘Go’ between ‘Paranoid Android’ and the second track. The track-listing of the singles may well be arbitrary, but the juxtaposition of the second CD, straight to the world of Kid A and strange noodling, is in a way more interesting and appropriate. The song, ‘A Reminder’, when it emerges is a folky little number surrounded with effects. The second track, ‘Melatonin’ maintains the sense of breathing on a planet different from OK Computer, or at least The Bends, with something of ‘Moon River’ in the melody.

OK Computer follows ‘Paranoid Android’ with ‘Subterranean Homesick Alien’, which sounds about right. The spacey and warm sound of the track, its slow pace, complements the scale and frantic exactitude of the previous track. ‘Warm summer air’ sets the scene and sense: the sound of an electric piano and a chromatic descent inside the harmony (the little path from the seventh through the major and minor sixth). With music like that, you could be saying ‘financial services act’ and it would still sound like warm, summer air. ‘Classical’ little motives lead to the repeats of the chorus in guitar: some of those guitar parts sound like parts of a Beethoven string quartet, Brahms even, with twos played against the triple metre. Words are again prose-like, a letter or a statement. Bob Dylan’s in the title but nowhere else to be found. ‘Lock up their spirits’ balances ‘live for their secrets’. The ‘folks back home’ sounds strangely prominent, as well as being a reference to Stephen Foster. The chorus is a good case of a very ordinary phrase, ‘I’m uptight’, magnified and made emotional by music and singing. I’m not so sure that the track comes off as a track, though it works well on the album.

‘Exit Music’ announces itself as film music, made for Baz Lurhmann’s film of Romeo and Juliet. Musically, it’s a simple repeat of the verse, twice, once, once, separated by two separate bridge passages, the first of which settles back in to set the ‘chill’ of the third verse, but the second of which is purposefully geared to build up to the soaring final verse. The verse is a simple harmonic descent, no problems there, something any guitarist might stumble upon. The bridges are nicely contrasted: the first one heads over to the area of the ‘four chord’, E, and plenty of padding out on slow ‘suspended’ chords (at 1’42” and 2’06”). The second is a grander affair, lending the song its Ennio Morricone flavour: first by using the ‘dominant of dominant’, C sharp, and then a very old trick, the ‘Neapolitan’ chord, C major, lurching onto F sharp for the big build up. (They’re a bunch of chords that return for ‘this is what you get’ in ‘Karma Police’.) The chords play with minor and major in a rather baroque manner, and the vocal lines occasionally sound to my ears like the Italian baroque; for the last verse, though, up the octave, it’s a later breed of Italian opera that’s recalled.

For people who know ‘Exit Music’ from Lurhmann’s film, the track may well be indelibly associated as film music. During the film the song appears over the final credits—lists run so long that one track isn’t enough!—and the speed of the appearance of the words corresponds to the slow pace of the song. Song and film track do, of course, live independently, and time will tell whether either lasts or lasts through the other. The Beatles are the textbook case of a band whose songs never get used in films, presumably for copyright-related reasons, so that however accurately a film creates a realist correspondence of a certain time (late 1960s or early 1970s) and place, its one absolutely guaranteed soundtrack element, a song by the Beatles, is absent. That said, Radiohead’s music does seem occasionally rather filmic, or visual, and further soundtrack appearances may follow.

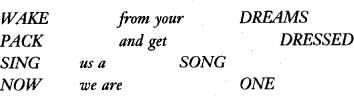

In ‘Exit Music’ there is a sense that words followed the music, but that the music in turn sets up its own hierarchy of prominent words. Here are the first lines of the verses:

‘Sing’ and ‘song’ balance each other, ‘now’ and ‘one’ recall each other. ‘Wake-dreams’ and ‘pack–dressed’ connect alliteratively. Now the second lines:

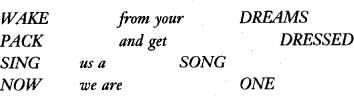

The first lines seem neater, the melody line for the second line taking two notes of the second line adapting to words in various ways. ‘Tears’ rhymes with ‘hears’, and ‘everlasting peace’ finally breaks the pattern altogether. That leaves the last lines: ‘today we escape’, ‘before all hell breaks loose’, ‘there’s such a chill’ and, echt Thom Yorke, ‘we hope that you choke’. Again, notice that these are largely ordinary turns of speech stuck into the pattern of the music. The middle sections follow this approach: the first has ‘breathe’ as a light word for the music, the ‘spineless laugh’ sounds right for that point. ‘We hope your rules and wisdom choke you’ is notably ‘stuck in’ to the melody line. ‘Choke’ obviously cancels out the breathing of the first bridge passage. ‘Exit Music’ thus seems like a carefully constructed song, perhaps more so than some of the more singable songs.

Let Down

Karma Police

Fitter Happier

Electioneering

The main claim of OK Computer as an album lies, I think, in its middle, where a run of three tracks suggests in turn three decent adjectives: expressive, thoughtful, and exciting. The core of the run goes from the latter half of ‘Karma Police’ through ‘Fitter Happier’ to the second verse of ‘Electioneering’. The trick had worked before, on The Bends, in the pairing of ‘Fake Plastic Trees’ and ‘Bones’, but the intervention of ‘Fitter Happier’ is crucial in giving the middle more solidity. Also, these tracks are dead centre, whereas The Bends might still have carried elements of the vinyl side in its track programming.

First, a track to link ‘Exit Music’ to ‘Karma Police’ and, as time goes by, ‘Let Down’ seems to me living up to its name. The chorus always seemed to me a bit abrupt: the rhyme ‘hanging around’ too close to ‘let down’, and ‘bug in the ground’ again too close to ‘around’. The music to the song, light and simple, finds it hard to bear the weight of all the band’s sweaty effort and production, although there are some cheery sound effects towards the end, as though it’s 1974 and Rick Wakeman has just popped in, fresh from one of his solo records. The problems start with the entry of bass and drums, with their heavy, four-beat emphasis, dragging down the delicacy, the systems subtleties of the introduction; the mix of the record adds to the ‘backgrounding’ of the guitar. During the second link, at 2’48”, the pedal note in the bass and festive percussion could form the basis of Radiohead’s Christmas single. It seems to me that something would have to happen harmonically to avoid dullness: the doubled vocal is also largely predictable ‘thirds’. Of the introduction (see the bar count), it should be said that this is rock music borrowing from minimalism, not a major change of aesthetic. By Kid A, the band as a whole would work together and follow such implications of the musical material but, on OK Computer, the call of stadium rock remained paramount. This is all a bit harsh: James Doheny is keen to see the song as a counterpart to ‘No Surprises’ and spots rhythmic links in the vocal part of the verses. Still, it fills the time nicely at this point in the record, and it’s a simple A major to A minor relation between it and ‘Karma Police’ where, in my view, the record heads into its decisive core.

‘Karma Police’ seems to me very much a story of two sections: the first is a bit lumpy, mock-scary, and maybe even plodding. Readers are advised to follow Doheny’s recommendation and listen to ‘Sexy Sadie’ on The Beatles of 1968 (the white album): the piano sounds and rhythm and the little harmonic twist just after ‘This is what you get’ in Radiohead (G–F sharp–C, at 1 ‘21 “-1 ‘26”) are both strikingly found on The Beatles. The chord sequence is strange, and doesn’t quite settle. All is progressing smoothly in a familiar, ploddy-ploddy, rock-music way. (Joni Mitchell has called that sort of bass playing ‘plahdy-plabdy’, which is in some ways better.) Big drums; and a good ‘here comes the noise’ moment at 1 ‘41”.

But then it changes. After the second chorus (from 2’30”) the track lifts, in various ways. Harmonically, there really is a key change of sorts (the sheet music charmingly follows the convention of preparing the reader for the new key signature), from E minor to B minor, although in truth both sections use similar chords. Then vocally or melodically, the key change takes Thom Yorke to his angelic register. Texturally, there’s a big shift, with all the instruments doing lighter things. Best to my mind though, there’s the one word, phew. Phew’s great: it’s a cartoon word, like ‘gulp’ or ‘zzzz’ or ‘bah’. Its precision matters, the fact that it’s really there, properly pronounced and not just sort-of-breathed, as we do. What’s happening is a genuine thing: the knowledge of karma police (whatever that is, or they are) has got so bad that as a solitary individual the singer has lost his sense of self (the solidity of sound giving way to levity). You could imagine saying ‘Phew!’ all the way from small things like a small faint brought on by physical exertion, through a momentary sense of stress getting the better of oneself, to some dreadful political suppression. The section uses a strong, churchy, piano-based chord sequence, like the ones in the Band’s ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’, or Bruce Springsteen’s ‘The River’. Good, old pop-music rules are observed: little vocal twirls (after the words have gone) not so far from the Supremes or Bananarama; and a walking bass not so far from a solid hymn tune like Vaughan Williams’ ‘Sine Nomine’ (’For all the saints who from their labours rest’). The track ends with a load of noise, however, serious-sounding stuff, and an immediate transition to the studio world of ‘Fitter Happier’.

‘Karma Police’ was the second CD single and so appears in several contexts. As noted in chapter one, the vinyl version of OK Computer has ‘Karma Police’ at the end of a side, and of course the two singles also progress differently from the track; so what sounds like an ideal progression to me, which is to cut from the noise ending of ‘Karma Police’ into ‘Fitter Happier’, is only one possibility. Like ‘No Surprises’, only one of the ‘Karma Police’ singles fills out with new material, the second CD being completed with remixes of ‘Climbing up the Walls’. On the first single, the track is followed by a slight track without words called ‘Meeting in the Aisle’ and a song called ‘Lull’. The former sounds a bit like middle-period Beatles, with the ‘No Surprises’ glockenspiel brought out over a simple chord sequence; like ‘Palo Alto’, it belongs very much to the world of OK Computer, and the album’s devotees would be well-advised to include it in their consideration. ‘Lull’ sounds unfinished, however, as if it still needs to develop: two verses, and then a sudden end—only 2’25”! Jonathan Glazer’s video for ‘Karma Police’ seems to add relatively little, unusual since Glazer as much as anyone took the promotional video to new expectations of what could be achieved: his earlier, monochrome video for ‘Street Spirit’ was a terrifically imaginative correspondence. The scene in the film of ‘Karma Police’ seems to evoke his remarkable film for ‘Rabbit in Your Headlights’ (1998) by UNKLE (which also had a vocal by Thom Yorke). The video happily mirrors the pace of ‘Karma Police’, and its sense of creepy surveillance; however, the focus on Thom Yorke in the back seat of a car, seemingly speaking the words in the typical mode of the video, seems disappointing in retrospect, while the video narrative refuses to correspond to the change in music described above. The best continuity from the track, by far, is found on the album: progressing from the second section of ‘Karma Police’ through the noise to ‘Fitter Happier’. On the vinyl version, the side change spoils everything, while the CD album progresses the concept, at this point. The character in ‘Karma Police’ is troubled, and here comes the reason.

‘Fitter Happier’ is a great example of what academics call electro-acoustic music, and the same could be said of the comparison as Ian MacDonald on the Beatles’ ‘Revolution #9’ (1968): ‘more aesthetically and politically astute … than most of the vaunted avant-garde composers of the time’. OHM: The Early Gurus of Electronic Music (Ellipsis Arts, 2000), a splendid compilation presenting the historical development of electronic music and musique concrète, was wittily dubbed ‘Jonny Greenwood’s record collection’ by Q magazine. The words of ‘Fitter Happier’ are terrific, showing at its best Thom Yorke’s knack of picking up phrases from real life and simply placing them in this arty context. Since the track is so very wordy, it plays a big part in the overall ‘image trail’ of the album. One interesting feature of the words as laid out, like a poem, in the sleeve-note, and kept in the sheet music, is the frequent presence of parentheses, making this a consistently two-voiced presentation, as well as making listening and reading slightly different things. Any possibility of actor-like ‘asides’, to correspond to the brackets in performance, is cancelled by the electronic effect, making the speech sound mechanical. Interestingly, the copyright attribution (see acknowledgment) has altered from the sheet music version, and includes Dan Rickwood, the Stanley Donwood of the album cover (see below).

As an arrangement of words, one thing to note is the care the track takes precisely to avoid any obvious euphony (rhyme or closely-placed alliteration or assonance). What takes its place seem to be clusters of grammatical categories: many of the ‘lines’ (and the lines continue into the performance) are observations made up largely of nouns or adjectives, without verbs or with the verbs acting adjectivally: ‘regular exercise at the gym (three days a week)’, ‘charity standing orders’, ‘an empowered and informed member of society (pragmatism not idealism)’, ‘no longer empty and frantic’. I’ll call this line type A. Balanced against this are the lines containing verbs, verbs which are in turn largely concerned with domestic detail (we’ll see more of this in the section on words): ‘getting on better with your associate employee contemporaries’, ‘eating well (no microwave dinners and saturated fats)’, ‘will not cry in public’. I’ll call this line type B: it’s mostly and firmly present tense, present and tense the album’s equivalent of present and correct.

Here are the lines taken from the sleeve note and numbered—I take the very first line as in the sleeve note as one line—the record reinforces this by bringing in sound effects for line two. I also follow the ‘text generation’ in their lack of capitals (though it pains me so to do):

Number of line (bold = includes parentheses)—line—(line type) and other observations—music (see chart)

1 fitter happier more productive (A)—voice alone

2 comfortable (A)—sound effects

3 not drinking too much (B)—negative

4 regular exercise at the gym (3 days a week) (A)

5 getting on better with your associate employee contemporaries (B)

6 at ease (A)

7 eating well (no more microwave dinners and saturated fats) (B)/(A—negative)—piano—B flat minor

8 a patient better driver (A)

9 a safer car (baby smiling in back seat) (A)/(B)

10 sleeping well (no bad dreams) (B)—(negative)

11 no paranoia (A)—negative

12 careful to all animals (never washing spiders down the plughole) (A)/(B—negative)

13 keep in contact with old friends (enjoy a drink or two now and then) (A)/(A)

14 will frequently check credit at (moral) bank (hole in wall) (B)—future tense. The two parentheses are of different nature—the first one an imputed characteristic, the second an observed feature.

15 favours for favours (A)—measure for measure

16 fond but not in love (A)—positive but negative

17 charity standing orders (A)—orders could be verb—charity orders all things

18 on sundays ring road supermarket (A)

19 (no killing moths or putting boiling water on the ants) (B)—negative, completely parenthetical—shift to G minor

20 car wash (also on sundays) (A)

21 no longer afraid of the dark (A)—negative (of sorts)

22 or midday shadows (A)

23 nothing so ridiculously teenage and desperate (A)—negative, nothing like the sun

24 nothing so childish (A)—negative

25 at a better pace (A)

26 slower and more calculated (A)

27 no chance of escape (A)—negative

28 now self-employed (A)

29 concerned (but powerless) (A)

30 an empowered and informed member of society (pragmatism not idealism) (A)—note past participles as descriptions. Isms: William James not Hegel, Richard Rorty not Jurgen Habermas.

31 will not cry in public (B)—future tense and negative

32 less chance of illness (A)

33 tyres that grip in the wet (shot of baby strapped in back seat) (B)/(B)—the photo both present and past

34 a good memory (A)—desirable but delicate human condition or an ok computer?

35 still cries at a good film (B)—‘still cries’ could, just about, be nouns …

36 still kisses with saliva (B)— … as could the kisses

37 no longer empty and frantic (A)—negative

38 like a cat (A)—‘like’ could be a command—‘Oi! Like that cat!’

39 tied to a stick (B)

40 that’s driven into (B)—back to B flat minor

41 frozen winter shit (the ability to laugh at weakness) (A)/(B)—‘laugh’ is an observed feature (cf 33)

42 calm (A)

43 fitter, healthier and more productive (A)—piano out

44 a pig (A)

45 in a cage (A)—‘being’ is implied

46 on antibiotics (A)—‘being’ is implied—followed by eight-second sound effect

Musically, things are fairly straightforward. There’s a little tune in the piano part, using three notes and an ‘octave displacement’, where the tune goes higher. The outline of chords sways between tonic and dominant. A common note, B flat, acts as a fulcrum for a shift from B flat minor to G minor and back again. It’s sounds like music to a French film, an effect added to by the technological effect on the piano part.

‘Electioneering’ then follows, a Radiohead belter. This track seems to belong to the rhythm section, the drummer especially. Like ‘Airbag’, it has a terrific, ordered intro (after the sound effects): slightly out-of-tune guitar riff (Robert Quine there somewhere, perhaps), drums and cowbell, top bass line (listen to it), and then voice. In fact, at the return to the second verse, there’s another little Beethoven quartet, classical-motive lead line in guitar (at 1’39”). The words are all about politicians on the make: I particularly like the vocal descent into ‘your vote’—it sounds like a very ‘cool’ and jazzy line but applied in a situation of great insincerity. A musical snarl. The forwards and backwards business of the chorus I don’t quite follow—are we going to do the hokey cokey?—and the ‘somewhere’ where we’re going to meet might have led to a ‘meet and greet’. Frankly, though, Phil Selway is already picking up Best Actor Award as the heavy-metal Beethoven of the seventh symphony’s finale, leaving Mr Books to worry about the government. Selway starts to develop an offbeat, second-beat emphasis like a George Foreman punch, something which gives Greenwood the rhythmic context carefully and precisely to throw caution to the wind. The slow interlude works well too, not least in giving Phil a fill return to die for: again, that interlude sounds like a disciplined string quartet playing hemi-demi-semi-quavers as though a silent film has someone about to throw themselves off a skyscraper. It’s tremendously exciting, and the idea of shouting out words, over and above it, effectively declaring that ‘politicians, by and large, suck’, is vastly entertaining. ‘Electioneering’ joins some of The Bends and OK Computer in leaving the listener speechless.

Climbing Up the Walls

No Surprises

These two tracks carry things along very well, with ‘No Surprises’ in particular acting as a somewhat lighter period between ‘Climbing up the Walls’ and ‘Lucky’. In turn, though, ‘Climbing up the Walls’ is a good shock-horror genre piece after ‘Electioneering’: the album’s running along nicely here.

‘Climbing up the Walls’ returns to the ‘gothic’ sense of parts of ‘Paranoid Android’ and ‘Exit Music’—slow, creepy, and less song than the sum of its sound effects: a good 46 seconds of its 4’46” gets taken up by the opening and ending. The words are a fine evocation of paranoia and surveillance, all locks and alarms, and worrying about the kids at night. But there’s more: the icepick and the ‘fifteen blows to the skull’ suggest real violence, though it’s never too clear what these people have done to deserve such attention. They’ve got kids, though, and are advised to watch them too. They tuck you up, your mum and dad.

Two remixes of ‘Climbing up the Walls’ get included as a follow-up to ‘Karma Police’ on the second single. Zero 7 return the track to Portishead-style creepy lounge music, uneasy listening, with a bit of a jazzy sample added in: all fine, if a little confusing. Fila Brazilia’s mix is a dubby-sounding context which foregrounds the vocal part, and actually shows what a big performance Yorke often does in the studio, something which the records gloss over. There’s some technical damage inflicted on the voice at 3’17”, a corollary to the character in the song. The remixes have all the time in the world, of which the first takes 5’ 15”, the second a marvellous 6’20”! Maybe it’s assumed that the listener has taken special tablets, or a day off.

‘No Surprises’ has a few surprises. F major is an unusual key for guitarists and the sheet music suggests that these are D chords transposed by a capo. Jonny Greenwood adds a glockenspiel, and there’s something of the air of orchestration. As we saw with the contrast of material in ‘Airbag’, there’s sure to be an element of dissonance as pretty music is going to contain words which are certainly not lyrical and, if the rest of the record’s anything to go by, lugubrious. Formally, the song has two verses followed by the short chorus of ‘no alarms and no surprises’. Fresh words after that are cut immediately into the chorus. There’s a very simple bridge section—chords to pad things out. Words and music are solidly out of joint: ‘bring down the government’ is the phrase that seems most obviously ‘stuck in’, with a musical stress laid on the third syllable of ‘government’. Other than that phrase, there seems to be a lot of internal alliteration, rhyme even (landfill/kill), all on the theme of h and 1: heart, full, landfill, slowly kills, bruises, heal, look, unhappy (the listener sure to hear both ‘an’ happy’ as well as ‘unhappy’), I’ll take, life, handshake, final fit, final bellyache, house, as well as recurring words ‘alarm’ and ‘silent’. Outside these sounding correspondences are some characteristic words: job, bruises, bring down the government, carbon monoxide, the pretty garden, and surprises itself. References to polity and science contrast with the ‘homes and gardens’, and these contrasts perhaps help make ‘No Surprises’ a track that’s characteristic of the album as a whole. But it’s probably the sound world, delicate and charming, that makes it distinctive.

‘No Surprises’ is the last of the OK Computer singles. On the album, ‘No Surprises’ offers a contrast to two doleful, minor-keyed, long and weighty tracks, on the singles the track comes first, of course, and so the effort of contrast or complementarity falls to the fillers. The second CD is genuine filler, two live performances (of ‘Airbag’ and ‘Lucky’): it’s interesting to hear this track cut back to the first one (in fact, there seems to be something from ‘Fitter Happier’ heard first). The first follows ‘No Surprises’ with ‘Palo Alto’, a big Radiohead track that would have graced the album (and altered its meaning): Doheny hears the Pixies; I can also strangely hear British beat groups of the sixties, the Who, maybe the Kinks. Then ‘How I Made My Millions’, a home demo that looks to a track like ‘True Love Waits’. The run of tracks on the first ‘No Surprises’ single is satisfying, as sometimes CD singles can be.

Grant Gee’s video for ‘No Surprises’ may well last as an interesting case, or at least an example of suffering for the art. This is the video where Thom Yorke is slowly drowned in water, held for a long time, and finally released only to have to mouth along to words of the last verse. It’s a compelling film, and rare in keeping the one shot throughout—Gee’s film Meeting People is Easy shows the video being filmed. Again, the pace of the action of the video, in this case the gradually and disturbingly rising water, seems to correspond to the music.

Lucky

The Tourist

OK Computer goes for the slow, ethereal ending. I’ve never been sure of ‘The Tourist’—‘hey, man, slow down’ doesn’t seem quite the sort of language these boys would ordinarily use: they’re admirably good at avoiding ‘ain’t’, for instance, and I can only presume that these are the words of an alter ego, the voice of the druggy sort of person which the music seems to be evoking as well. The verses seem to be filler words, ‘a-flowin’ ‘a peculiar anachronism. The dog completes the menagerie of the album: maybe there was a memory of Dylan’s ‘down the streets the dogs are barking’ in the ‘a-flowin’ ‘. The music is nicely airy and lambent and glassy, all open fifths and queasy lurches in the harmony. I suppose it’s left deliberately ‘static’, though personally I could have done with some more detail or events, or just something to keep me from falling asleep. For an album that has scaled heights with impressive daring, ‘The Tourist’ seems just a bit too soft and comfortable for the purpose. Actually, the very ending is notably duff: bass and drums giving way to a single triangle. The world ends with a whimper not a bang, assuredly, but there just seems something a bit ‘youth orchestra’ about that triangle.

‘Lucky’, on the other hand, seems to ‘do Radiohead’ in a short space of time. Again, it’s a really good idea—surviving a plane crash and feeling elatedly happy: well, why not? Dead people strewn around, corpses and blood, but you were on your own and they’re all people you don’t know and won’t grieve for. The music is not so far from the discussion earlier in ‘Karma Police’—there are those couple of singalong chords, first heard at ‘I feel my luck’ and later becoming heartily sung. Again, the harmonic language is not so far from church. The chorus goes into ‘airy’ modals again, and technology reinforces this with wibbly effects. An expressive bridge sees the guitar going into its expressive bottom range. In the words, the ‘Sarah’ figure is a notable proper name for the record, though musically she’s forced to be ‘Say-rah’. (Whatever will be, will be.) A sequence of phrases bunch together: ‘on a roll’, ‘of the lake’, ‘on the edge’, and ‘of the aircrash’. Against that are the more marked phrases: ‘luck could change’, ‘again with love’, ‘me by name’, ‘time for him’, and ‘glorious day’. ‘Kill me again with love’ is probably the weirdest line, especially after Sarah with her strange emphasis. The way the music works out means that the song ends on a questioning dominant chord, an ‘imperfect cadence’ as the theory exams used to put it. Actually, if the listener hums the last note of the singer’s line in ‘Lucky’—take a bit of a breath, the gap lasts nine seconds—the same note will become the keynote for ‘The Tourist’.

‘Lucky’ appeared on a charity single as early as 1995 where it was followed by the excellent PJ Harvey and a live and fast ‘50 foot Queenie’. A concert version of ‘Lucky’ follows a live ‘Airbag’ on the second ‘No Surprises’ single. The song is made for live presentation, and on this recording the words are more clearly heard; the ‘glorious day’ of verse four is always most affecting.

Saying things about each song or chunk leaves unattended the idea that an album may be experienced, heard or considered as a single whole. Music and words work in rather different ways in this respect, while the record’s artwork will confirm or impose its own unity on the disparate elements.

OK Computer has a particularly notable visual design, which has already featured in a ‘best ever’ collection (Q magazine’s 100 Best Record Covers of All Time, 2001) and is likely in my view to continue doing so as long as people care and obsess about these things. OK Computer was a leap forward from previous Radiohead covers, and extended the alliance of Thom Yorke, now as graduate in Fine Art (in addition to English), with Stanley Donwood. The team went on to greater things with Kid A, Amnesiac, and Hail to the Thief, forming a body of art-music pairings which possibly already, or might in time, parallel Storm Thorgerson’s alliance with Pink Floyd. These are the days of mass participation in art criticism and, at the time of writing, there is a website devoted to the cover of OK Computer alone. In talking about album covers, I suppose one affects the hat of the art historian or, nowadays, ‘observer of visual culture’.

The first point I would make of the OK Computer album cover, by now not surprisingly, is that it makes a virtue of the CD format. The art of album covers depended, it seems to me, partly on the dimensions of the 12” record and its relation to our human sense of proportion—even our size! By the time OK Computer came along, the tricks of the CD cover had surely been learned: the tendency was for the sleeve to fold out, emphasizing its nature as oblong rather than square—sometimes the extensions were very long indeed, and the reader had to be something of a piano accordionist. Conversely, as with OK Computer, the additions were made into a book, pinned together with staples, inviting comparison with art books or even ‘artist books’, a sub-genre in the modern art world. The art of the CD album cover preserves one principle from the vinyl cover (or two-dimensional art in general, I presume): the careful balance of generality and specificity of detail. The famous Roger Dean landscapes for Yes and Osibisa in the 1970s were of a particular kind, with relatively little, and thus pointed, specific detail inhabiting their lunar backgrounds, which evoked Dali and de Chirico. OK Computer, conversely and, it would seem, deliberately, crams the space with detail in a method which seems to owe something to collage. The distant precursor of this cover would seem to me the ‘synthetic’ cubist paintings of Picasso around 1913.

There are 12 pages of artwork, ordered five opening, the middle (’pages’ 12–13), and then five ending (20–24). There are two more on the CD base. (Whether the number is intended to correspond to the number of tracks, and their sectional nature, is up to you.) The intervening pages, 6–11, and 14–19, are taken up with words and, at page 19, words, credits, and a summary of little logo figures. It would appear that 4–5 and 20–21 may be double pairs, oblongs rather than squares but, since the artwork is unified as a whole, that distinction is difficult to maintain. The collage seems to be made up of the following elements:

1 logo figures, many gathered together at 19.

2 text, which uses a range of fonts, languages and is sometimes electronic sometimes handwritten

3 drawings, often evoking the world of urban planning or industrial design

4 photographs—the motorway on the cover, a factory worker at 4, the beach at 20, aeroplanes at 23, the ‘art photo’ of a tree at 24. At 3 there’s a photograph of a family gazing at a marble Jesus.

5 general colour or paint: besides black and white, blue is clearly the dominant colour. The colour ‘bank’ seems to be indicated at 24.

The design principles of the album carried through to all of the singles, adding a further six pages, albeit three times two, with different colours and detailing. The second ‘No Surprises’ single is a particular surprise in bright yellow and without a clear indication of its nature as second CD. All the singles and the album cover contain the black X on blue on the front. The vinyl version of the album selects six images in all: front and back cover correspond to front and back of the CD, with the back page of the CD book, its page 24, as one of the four inside-sleeve images, along with pages 21, 22, and 23 of the CD book. The computer-like words and credits appear as the inside of the album cover. The images are, obviously, bigger, but they do seem also to be ‘blown up’, and perhaps lose the ‘squashed-up’ precision of the CD images.

But what does it all ‘mean’? One point is that the artwork brings out the title of the record clearly. Consistent with many bands at this time, a ‘band logo’ was de rigeur—so that the print of Radiohead itself on OK Computer corresponded to The Bends and lasted, just about, into Kid A and Amnesiac. For OK Computer, this is a matter for the titles alone: the words for the songs are rendered as computer text; in fact, the album cover’s text is probably the most explicit use of the computer of the title. It’s well worth observing that, since Pablo Honey, no Radiohead album or single has featured photographs of the band. This is the world of band as brand, a practice that I would guess Radiohead inherited from Peter Saville’s designs for Joy Division or New Order and the Factory label; or from various bands on the 4AD label. It’s obviously an ‘art’-derived view of things, but also (and here the detail counts) assumes an audience which is actually going to observe and pick up on detail.

In turn, of course, the covers evoke thematic elements which can also be heard in listening. The dangers of driving and flying are evoked in the idealised, failsafe world of photographs and industrial design; the tacky marble Jesus loves the kitschy child of the family; there’s plenty of ‘big brother’ surveillance and looming threat; and a degree of poignancy. To take a single example, in the image at page 20, a family holiday is evoked through the beach photo and a childlike drawing of a house (family and safety). However, a blue/black alien seems to be landing onto a blue/black ground, brooding and far more present than the earthly, human memories and sketches. White brushstrokes seem to depict a sort of TV ‘fuzz’ which you wish would go away, the interference on a radio which is ‘detuned’. The colour blue itself, as used on the cover, would merit study in its own right.

The words on Radiohead records belong, like the artwork, to Thom Yorke, and the band is in this important sense, as they might have said in the beat-group 60s, Tommy York and the Radioheads. The association of the words with one person has peculiar effects on our conception of the band as a whole, which tends to be a singularity or a happy democracy working together. We tend to think of the Smiths as being opposed to the monarchy, staunchly vegetarian, and diffident about sexual matters in general, but it doesn’t follow that every member of the group thought so. One of them did, of that there can be no doubt. Mick Farren is good on this aspect in his memoir, finding to his understandable surprise that members of his band the Deviants, despite looking like paid-up participants, in fact ‘didn’t believe a word of this counterculture malarkey, and were only embracing the trend as another avenue to rock-business success’. Later too: ‘in theory, the Deviants were a democratic, egalitarian unit; all for one and one for all; all the lads created equal. Unfortunately, that only extended to the fun stuff. In matters of money, I was suddenly the scapegoat again’. I doubt very much that the latter, fiscal point has so much force in Radiohead’s case, though the track record of bands eventually turning up in suits and ties to complain to the court about financial matters wouldn’t inspire confidence, but there’s a real tension to my mind, an intellectual one, between the role played by Yorke in OK Computer and the role of the other four. For what it’s worth, I don’t consider that the words have quite that significance or neatness, and reckon the others could just as easily chip in. Thom Yorke is less a songwriter to my mind than a peculiar thing, an ‘idea-led word-producer’, the words important as things in themselves rather than necessarily for their place in the song.

Elsewhere I’ve called this style of songwriting ‘anti-lyric’, where words are more like prose than like poetry, characterized more by the singularity of the words themselves rather than the way they fit in to the song as a whole. A good example is the Gang of Four’s great record, Entertainment!, containing, right from the start, loads of individual words or phrases one simply wouldn’t have expected to find in a pop song. The same was true of the Smiths: ‘This Charming Man’ introduced more and fresher words in two minutes than entire outputs had for years, and did seem to make a lot of songwriters look redundant overnight. In turn, this theory implies a sense of genre crossover—a songwriter (as ‘word-supplier’) finding some possibly consistent source outside the concerns of the traditional lyric; cartography, for instance, might be a good example of an area relatively untouched by song (if it wasn’t for ‘Map Ref. 41° N 93° W’ on 154 (1979) by Wire). Considerable pressure is thus placed on the songwriter to carve out that consistent space: Ian MacDonald sees such song-writing individualism negatively, as:

a loosening of standards in the lyric aspect. The words of pop songs became freer in subject matter and ambition of expression, but with this came a wilder attitude towards the sense of lyrics and an increasing willingness to be idiosyncratic or wilfully obscure.

This begs the question: whose standards, those of Cole Porter (the standard of standards), Carole King or Paul McCartney, or Morrissey? All of them are crucially different. A good case to see how much you’re going to worry about this aspect is the phrase ‘bring down the government, they don’t speak for us’ in ‘No Surprises’, which does seem like a phrase external to the song and merely stuck in, so that it runs against any given or mellifluous expectation on the part of the lyric. On the other hand, it jars by its awkwardness, and brings the jaded ennui of the narrator into line with world affairs.

OK Computer certainly has plenty of distinctive words and ideas as it progresses. The title is rather inappropriate, really, unless it’s taken to point towards the way that computers act as a screen on which to view life as it goes by. A more accurate, if rather academic title might be: ‘Domesticity, Transport, and Human Freedom’. Domesticity matters a surprising amount. Cars and freedom were familiar tropes, especially in American pop culture from Chuck Berry and Jack Kerouac, through Easy Rider and the Joni Mitchell of Hejira, to Thelma and Louise. OK Computer has a lot to do with the private world, the body and the world of the mind and emotions, stretching out to friends and relatives and pets. Transport is important: that’s the thing that enables you to move, literally and metaphorically, but transport is also very dangerous. Freedom is in turn something you want but can’t have: the character in the record can’t work out if he’d be better off going back to his house and friends or whether to go outside, since so much of the world sucks. In particular, the government of the day seems to be stifling, rather than supporting, this vague sense of democracy and well-being. It’s not entirely fanciful to imagine the persona of OK Computer among the younger generation depicted in Robert Putnam’s great and epochal study, Bowling Alone: bored, purposeless, passive (all thanks to my generation), but also itching to change things without quite knowing where to start.

An ‘image trail’ of the album reveals the following, grouped under unifying headings. They’re all found in ‘Fitter Happier’ which is, of course, very wordy throughout:

1 home and gadgets: floor (collapsing), fridge, radio, bottles, walls, key, lock, toys, basement, cupboard, alarm, house, garden [FH: microwave, film, cage]

2 other people: yuppies, friends, father, Sarah, superhero, her (face), kids, friends, man, idiot [FH: associate employee, baby, old friends]

3 the body: sleep, rest, voices, head, legs, skin, screaming, vomit, breath, smell, dreams, tears, laugh, spine(less), choke, hairdo, fit, face, skull, smile, eyes, bellyache, heart, bruises, handshake [FH: eating, drinking, exercise at gym, sleeping, cry, illness, (good) memory, cries, kisses, saliva, shit, laugh]

4 moods and states: (ok), born again, panic, weird, paranoid, alright, uptight, sentimental (drivel), hysterical, panic, alarm, lucky, kill me again, love [FH: fit, happy, getting on, at ease, (no) paranoia, fond, afraid, teenage, desperate, childish, concerned, powerless, empowered, informed, empty, frantic, weakness, calm]

5 animals and insects: chicken, pig (and piggy), creatures, wings, bug, ants, a cat, a pig, cattle (prods), and (though not named as such), a dog (barks) [FH: animals, spiders, moths, ants, cat, pig]

6 transport and travel: juggernaut, car, airbag, driving, ship, transport, motorways, tramlines, tyres, driver, motorways, car wash, flying, aircrash [FH: driver, car, ring road, car wash, tyres]

7 science and technology: (computer), chemical reaction, maths, antibodies, microwave, saturated fats, carbon monoxide [FH: saturated fats, antibiotics]

8 nature, outer space, and mystic things: inter-stellar, universe, android, rain, God, country lane, stars, aliens, hell, ghost [FH: the dark, midday shadows, wet, stick, frozen winter]

9 the public world: world war, German, networking, police, Hitler, payroll, electioneering, vote, riot (shields), (voodoo) economics, business, the IMF, government, head of state [FH: associate employee, bank, charity, supermarket, self-employed, pragmatism, idealism, empowered, informed, society, public, productive]

Maybe what distinguishes the mind-world of OK Computer is a sort of ‘existential realism’, a world of tiny detail, sometimes poignant—little things can be the most affecting—but overlaid with a high emotional temperature. The latter gets boosted, of course, by Radiohead’s music and Thom Yorke’s voice, returning us to Paul Simon’s dichotomy of ordinary and enriched language in the song. At the extremes of this world are expression and realism. It’s an explosive mixture, for sure, a source that art constantly revisits and reconfigures. And if the sleeve’s collages evoke the world being observed, then it’s only the observed distance which lies before a figure like that in the foreground of the Caspar David Friedrich painting ‘The Wanderer above the Mists’ of 1818: we’re all standing on the edge, but behind Thom Yorke, who’s doing all the looking for us.

Musical continuity, or at least the demonstration of musical continuity, in any kind of work (our album) made up of individual pieces which also stand alone (our tracks and songs) can happen only in certain ways. In the analysis of tonal music there have been essentially two winners: one is to suggest lots of ‘motivic’ connection, little bits of melody or rhythm that recur; and the other, not unrelated, is to suggest that all tonal music is of its nature unified by being in a key, and the same unity is found in any piece which defines itself in that way. The clearest demonstration of the latter is found in the representations of pieces devised by Heinrich Schenker in the first decades of the twentieth century. He thought the system he devised closely related to the evaluation of masterworks, and would never in a millenium have considered rock music in that light; nevertheless, music theorists have adapted his methods to rock music, as well as to pre-classical and modernist music. Like going to see Radiohead play live (for the band and for the ticket agency), there’s a double price to pay to enter Schenker’s realm: one is that you have to be able to read music, and the other is that you have to understand the presentational details of Schenker’s system, precise and sensible as they are. What I’ll do here is try to translate some of the things these analytical systems might have to say about OK Computer.

It helps to start from the idea that the musical language of OK Computer is a hybrid, and it may be worth thinking through how the music actually appears. It surely starts from a guitar-led songwriter, who occasionally takes himself to the piano but, I think, like Bob Dylan, still approaches the piano as a guitarist. So the music is basically a succession of chords, and the chords in turn sit in one particular area of the spectrum of pitch: that played by guitar chords. Also, the guitar invites two other relevant things: it’s easier to play certain keys and difficult to modulate in certain directions, and it invites a highly ‘vertical’ kind of succession of chords. Piano-based music first has tremendous modulating facility; it also has a propensity to emphasize voice or line over the succession of chords—the piano keeps the bass part in check. Where the guitar leaves the piano standing is as a rhythm instrument: it’s much easier to play rapid successions of chords and notes; the bass player has some freedom as well, which may be a good thing.

What then happens is that everyone else adds in elements to the central ‘song’. (Sometimes Radiohead songs do still sound like busker-style, singer-songwriter songs: tracks 9–11 of The Bends have always struck me in that way—it’s where that album runs out of steam.) The bass part matters enormously and has a degree of independence—an element that increased after OK Computer (in fact, all of these elements tended to increase afterwards). Guitars, in the second or third guitar parts, furnish many of the sound effects, but don’t always necessarily affect the pitch content of the songs. The drums work both as defenders of the beat and, like the bass part, to supply motivic elements or reinforcements: after OK Computer, the drums, conversely, tended to lose out to programmed rhythms. For all the musical additions and production details, chords themselves never really change, which makes the sheet music, although only containing guitar parts, a pretty dependable guide. In fact, what this album sounds like as ‘pure music’, music without words, can be checked by listening to the recording of OK Computer in its entirety by a string quartet, and there’ll be further discussion of that in the final chapter.

The central language, the Radiohead sound world, is similar to many rock bands: centred in the minor key, and using a flexible modal language where the ‘seventh degree of the scale’ is usually flattened. Sometimes a major 4 chord can appear in the minor context. Conversely, moving from a major chord to the ‘flat fourth’ links the main progression of ‘Airbag’ to the start of ‘No Surprises’. When in the major key, chord sequences tend to be solid and grounded: they allow for mellifluous doublings of voice parts. It’s possible to hear the ringing sound of an added second (what Steely Dan would call the ‘moo-chord’) at the end of ‘Airbag’ and ‘The Tourist’ acting as sound bookends for the album. There’s a thumbprint in ‘No Surprises’: the progression of tonic to ‘chord four with added major seventh in first inversion’ (or ‘the relative minor with an added sixth’) had appeared in ‘Fake Plastic Trees’ and would reappear in ‘True Love Waits’. Its poignancy may have something to do with the second chord being a mixture of major and minor. Some more peculiar chord sequences—‘Subterranean Homesick Alien’ starts with a ‘tritone relation’, while ‘Fitter Happier’ has a ‘minor third relation’.

As we move into more melodic or contrapuntal elements (melodies in combination), further traces arise. A descending chromatic progression is sometimes found: ‘Exit Music’, the slow section of ‘Paranoid Android’, and the inner voice of ‘Subterranean Homesick Alien’. Another melodic thumbprint is the decorative figure of the ‘turn’—on a piano, E-D-C-D-C: listen to ‘Airbag’ at the start and the wordless vocals at the end of ‘Karma Police’. The main riff of ‘Paranoid Android’ (section B) includes the fairly ambiguous, ‘spooky’ cluster (A flat, C, D). The vocal line in turn is often characterized by stepwise melodic descent (sing ‘God Rest, ye Merry Gentlemen’ to hear some nice examples).

‘The Tourist’ uses a more lambent harmony, made up of open fifths and lurching descents. This breathes the air of a different, if not especially distant, planet. Make no mistake, however, the next two albums really do go much further in musical material than OK Computer.

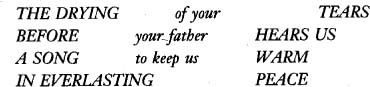

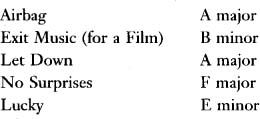

Whether, beyond that as a ‘given’ premise, one actually forms musical links across tracks, is highly debatable. Let’s review the tonal arrangement of the tracks first:

These are mostly keys that derive from the guitar chords. Of the harmonic centres, the clearest, most stable songs are, most likely:

And that, I think, is it: it seems to me as difficult to suggest continuity between tracks as it may be in the symphony between movements. The best comment on the musical shape of the album as a singularity may well be found in Larkin’s observations about poetry books: letting the individual tracks live together with some view to contrast, while keeping an eye on the big moments of start, middle, and end. What I think one does hear across the tracks are the proportional relations of wordy and wordless sections, and the relative amount of contrast supplied by instrumental breaks and sound effects. To close our review of the music, I shall just bring these last two elements together.

It’s worth gathering these together since they form a lot of the padding of time across the album. The musician most associated with these is Jonny Greenwood, though that may downplay the role played by O’Brien in the three-guitar line-up. Nevertheless, nothing in the Radiohead output, OK Computer included, matches the ferocity of Greenwood’s breaks on ‘My Iron Lung’ from The Bends—‘Electioneering’ coming the closest, perhaps. Significant and substantial break sections are found in the following tracks:

Airbag—intro, two separate break sections, and coda

Paranoid Android—intro and three separate break sections to coda

Subterranean Homesick Alien—intro, a link section, and coda

Let Down—intro, link sections, and coda

Electioneering—intro, link, break, and substantial break to coda

Climbing Up the Walls—intro, one break section into coda, long coda

No Surprises—intro, short break section

Lucky—break section

The Tourist—intro, link sections, and coda

Of those, the really notable breaks, where the break isn’t simply a link, are found in: ‘Airbag’, ‘Paranoid Android’, ‘Electioneering’, ‘Climbing up the Walls’, and ‘Lucky’.

I’m not so sure about these bits, though they certainly pad out the time. One of the big arguments in getting popular music studied properly is that timbre-based aspects of music get downplayed by an over-emphasis on notational detail such as chords. However, I think there’s still a problem in getting electro-acoustic music and the traditional tune-and-accompaniment type of music to co-exist in the same piece. So, frankly, ‘Lucky’ to me actually gets going twenty seconds in with the strumming of the E minor chord, an even more dramatic impression when the song gets performed in concert. Again, I think this issue gets confronted more interestingly and directly in the next record, Kid A, although actual, stand-alone electro-acoustic pieces tend to imply different performance contexts from the stadiums which became filled with songs from The Bends and OK Computer.

Found at: the end of ‘Karma Police’ (at least ten seconds), the end of ‘Fitter Happier’ (eight seconds), the start of ‘Electioneering’ (thirteen seconds), the opening of ‘Climbing up the Walls’ (eleven seconds), the end of ‘Climbing up the Walls’ (at least thirty-five seconds), the start of ‘Lucky’ (twenty seconds)

Individual tracks speak for themselves. To state the obvious, OK Computer is a diverse collection given greater unity by its context as an album. CD as format preserves the familiar emphasis of start and end, but invites an attendance to the intervening stages and their possible sense of continuity and progression. Does it come off? To put that question another way: will the album last? Time to stare out of the window. Time to ponder.